1872年東京 日本橋

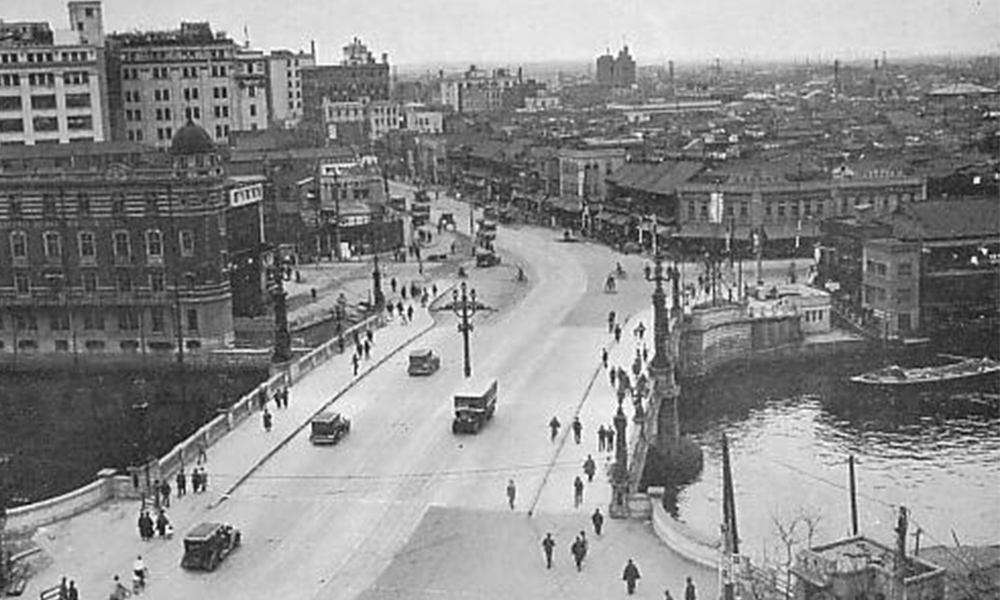

1933年東京 日本橋

1946年東京 日本橋

2017年東京 日本橋

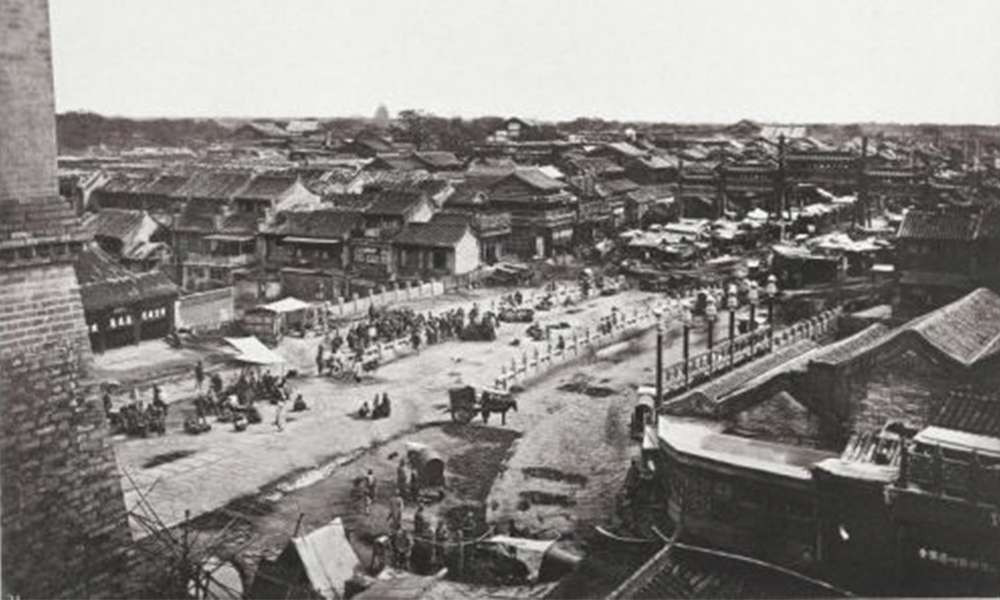

1872年8月〜10月北京 前門

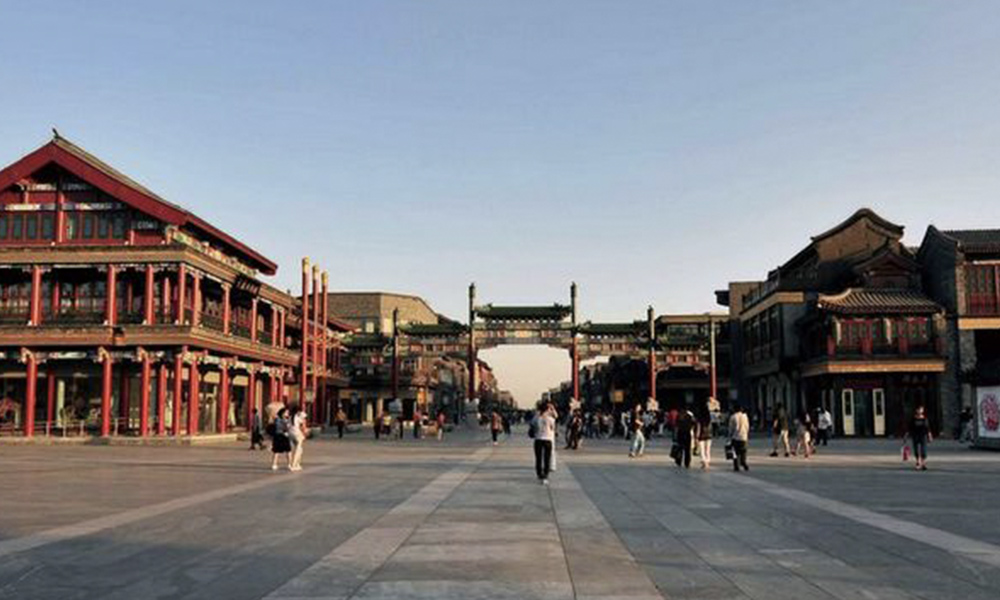

現在北京 前門

1949年前後北京 前門

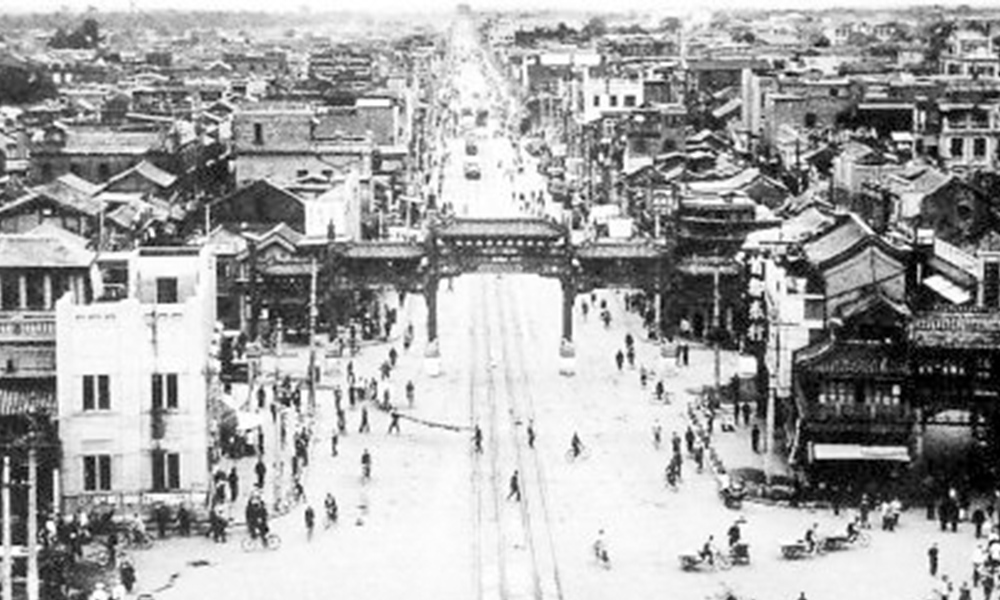

1930年代北京 前門

1895年台北 衡陽路

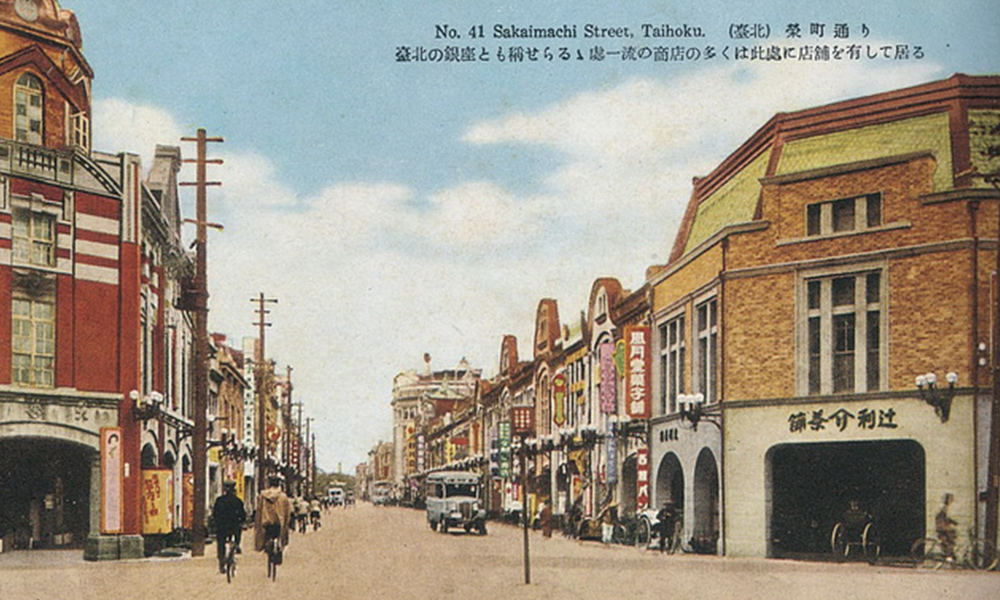

1930年代台北 衡陽路

1960年代台北 衡陽路

現在台北 衡陽路

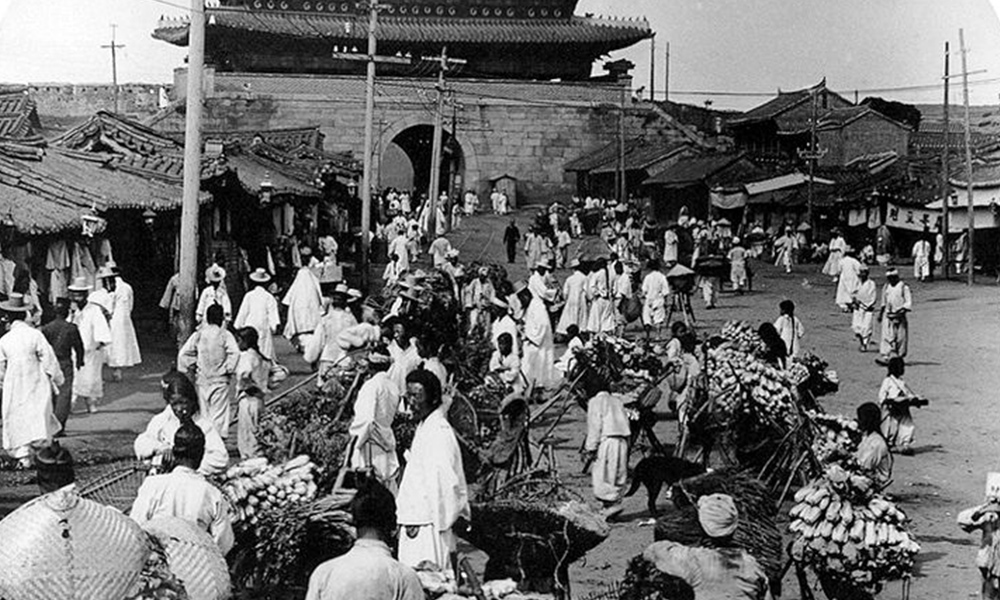

1904年ソウル 南大門

2006年ソウル 南大門

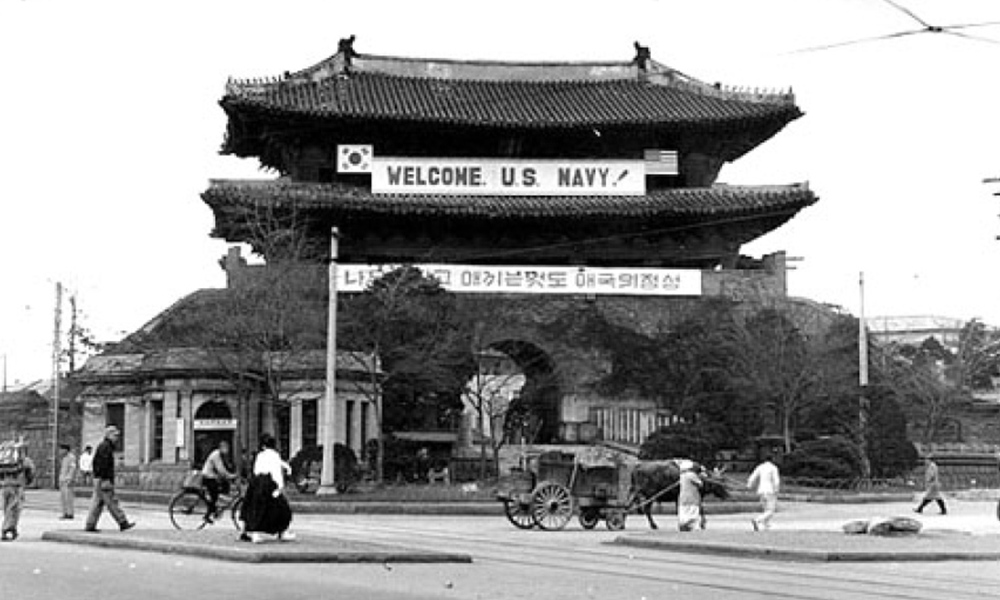

1950年ソウル 南大門

1940年代初ソウル 南大門

Cho Ryoon Ja, Pansori Drummer and Playwriter

I lived in Jeju Island from 2003 to 2005. I was teaching Japanese language at Jeju National University.

I was born to a third-generation Japanese-Korean in Osaka, but I had not known at all about ‘Jeju April 3’ until I began to live in this island. Even I’d never heard about the word ‘Jeju April 3’. Both of my parents from the Peninsula and I was born in Japan, so that I had no chance to acknowledge about Jeju Island. Therefore, I even did not have prejudice. My mother understood the Island as a traditional place of exile. Her understanding was gained from TV drama, ‘Dae Jang Geum’. Therefore, Jeju Island was nothing to do with my life and was far away from me.

It was around when a moth had passed since I started to work at Jeju National University. I finished my work and got out the school building. I walked through outside building of a student union. On a notice board, there was a number of newspapers, some of which mentioned about students protest against tuition fees. I often saw and became familiar with such stories. However, I realised that there was unusual report, which margins were in black.

It was a newspaper about ‘Jeju April 3’.

I was confused. Was it about a novel? I could not believe that such uprising was occurred in the past in this island. I questioned myself. Why I didn’t know such huge incident and why nobody told me about this tragedy. I couldn’t understand my circumstance that I was facing at that moment.

During my holidays, I went back to Japan, and began to search documents about ‘Jeju April 3’, and read them. I leant for the first time that many Japanese-Koreans in Osaka, were from Jeju Islands, and in fact, many of them escaped from the uprising. I also learnt the reason why it had not been told amongst people. This was because the uprising was very cruel. I was depressed with such absurdity.

In October 2003, President Roh Moo-hyun visited Jeju Island and officially apologised for the fist time as President. Even his apology, no body talked about ‘Jeju April 3’, and asked me about the uprising if I would have known about the event in the past, during my stay in the island. Perhaps, everybody was reluctant to tell about the incident, because I was from Japan as Korean-Japanese. After all, until my return to Japan in 2005, I could not have asked to people and have talked about ‘Jeju April 3’ in Jeju Island. Furthermore, I had never re-visited the island until I performed ‘April Story’ this time. Indeed, I could have not visit Jeju Island without dealing with ‘Jeju April 3’. Jeju Island became a core phenomenon in my mind.

After my return to Japan, I met Ahn Sung Min. When I was an university student, I learnt a percussion instrument, so I decided to play a drum for Pansori with her. Nowadays, Pansori is known as one of traditional entertainments, and it is often performed at a big hall. However, it used to be performed on a road for the public, and it satirically sang a song about people’s daily lives and feelings such as happiness, anger and sadness. It was made with audiences and created a special moment. When I began to perform Pansori, I became wanting to write Pansori about our stories of Japanese-Koreans.

We had an opportunity to perform ‘April Story’ during the opening ceremony of the meeting to listen to testimonies of survivors. The event was held as a part of the 70th Memorial Service of the uprising, and was organised by a research institute of Jeju April 3. If I am right, our participation was decided in November 2017. At that moment, I did not event started to write a script. The performance was planned to play in the end of March 2018. I was a bit wo+

rried… However, I did not have choice. I had to do. Fourteen years have already passed since I knew ‘Jeju April 3’ on the notice board at a student union. I thought that if I lost this opportunity to play, I won’t compete to write Pansori about the uprising, and I could not accept such incompleteness with me.

It was very hard work for me to read records about ‘Jeju April 3’ in a short period of time. I had to face experiences of victims and survivors. I sometimes almost cried but tried not to cry. It was a story about people who could not cry when they wanted to cry. I believed that if I cry or talk about the story, I would not be criticised.