1872年東京 日本橋

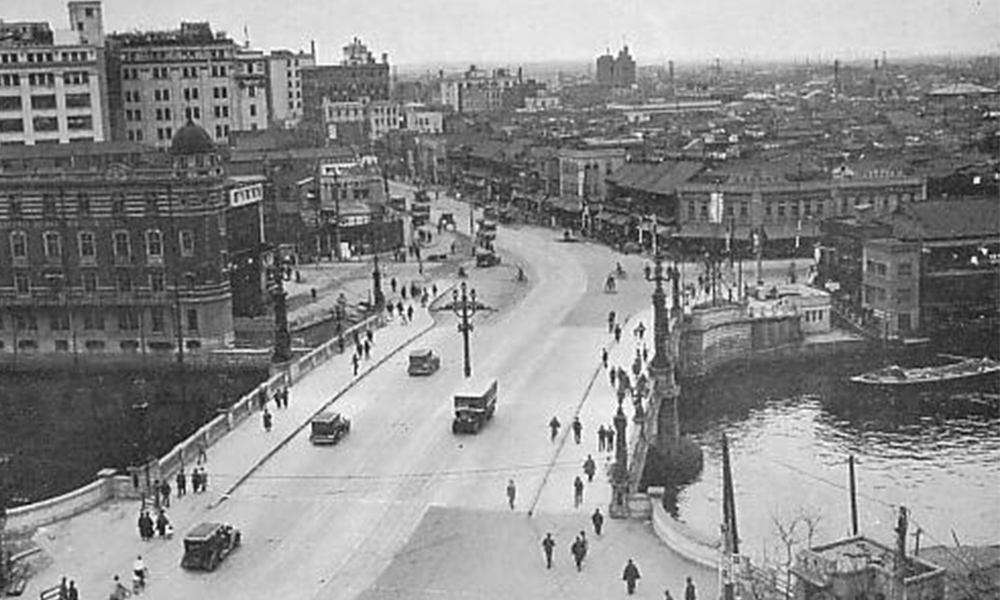

1933年東京 日本橋

1946年東京 日本橋

2017年東京 日本橋

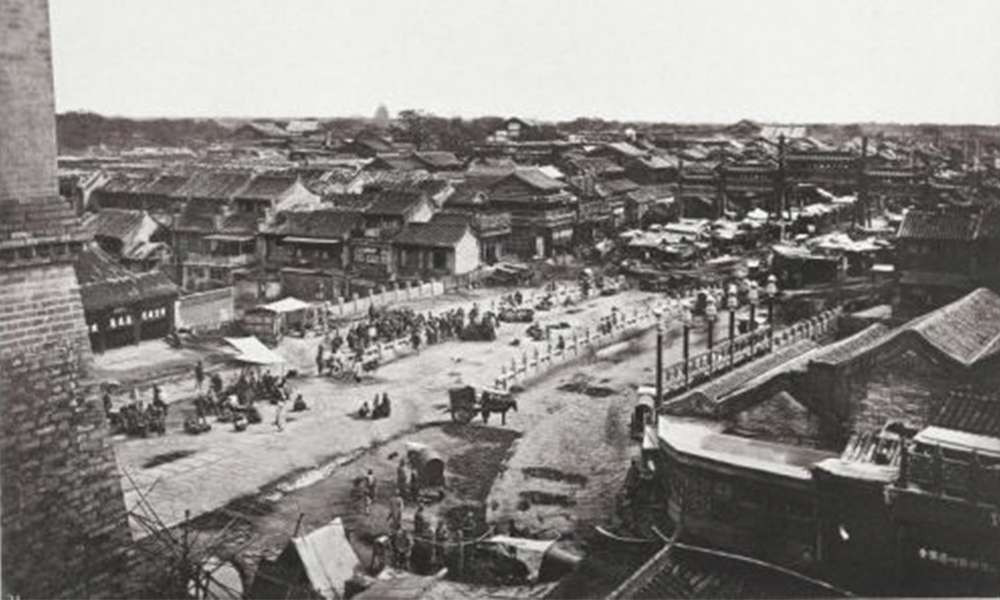

1872年8月〜10月北京 前門

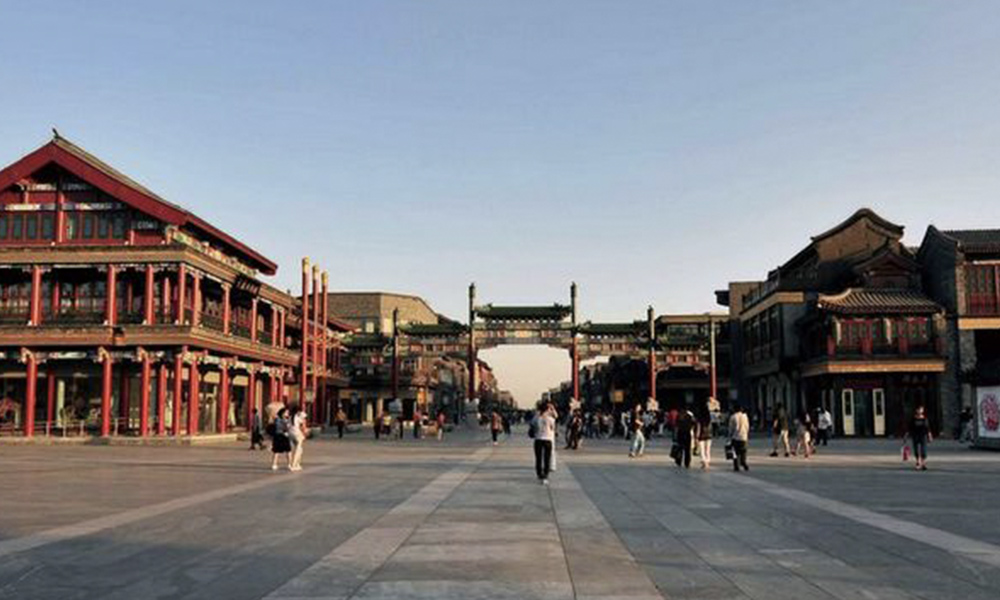

現在北京 前門

1949年前後北京 前門

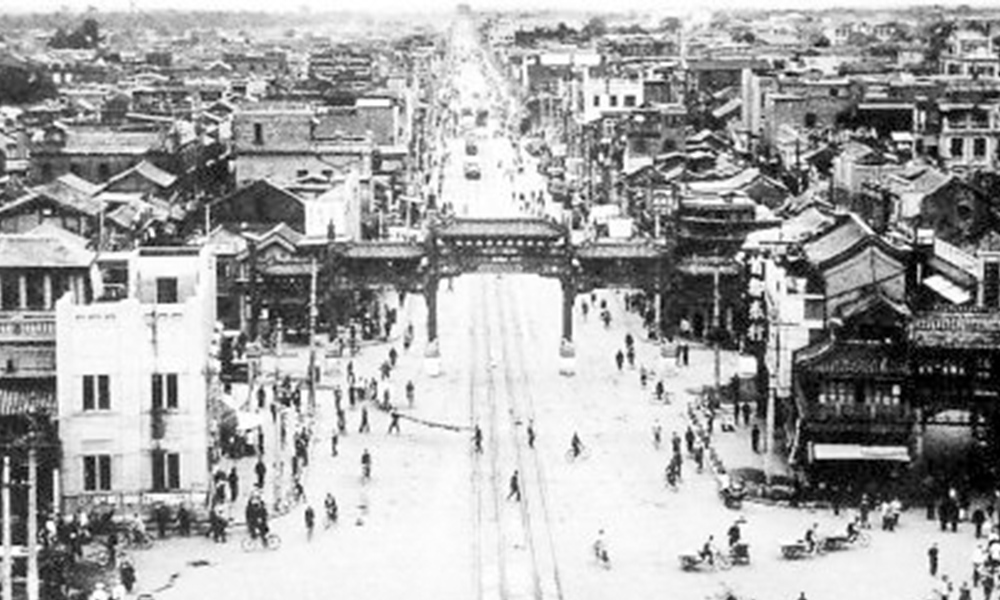

1930年代北京 前門

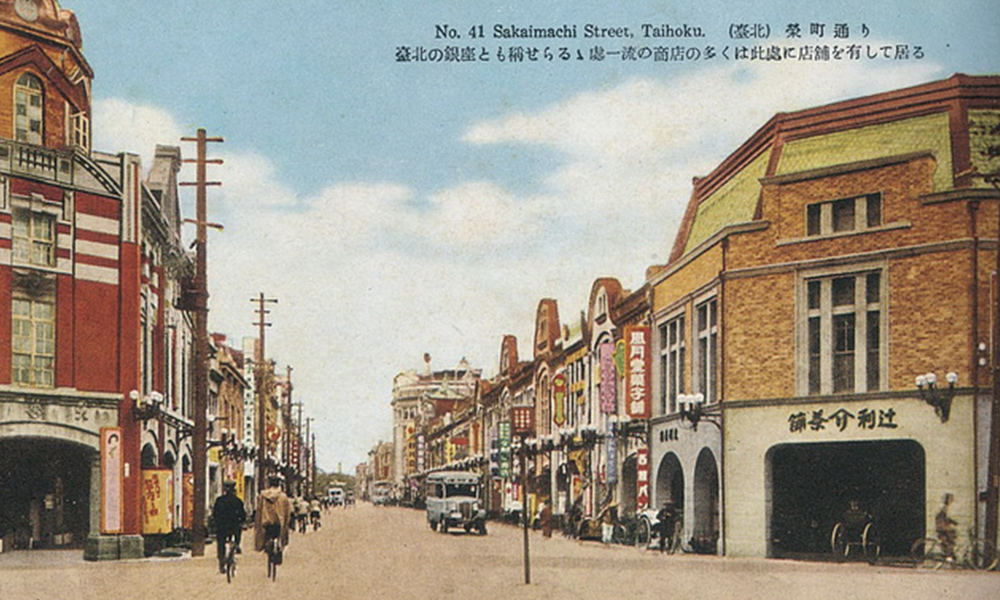

1895年台北 衡陽路

1930年代台北 衡陽路

1960年代台北 衡陽路

現在台北 衡陽路

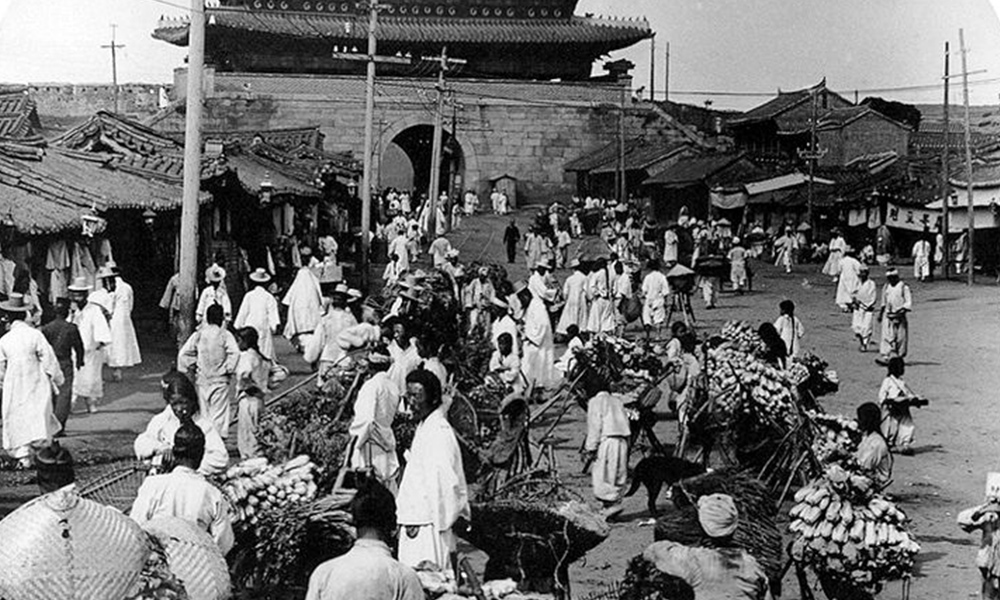

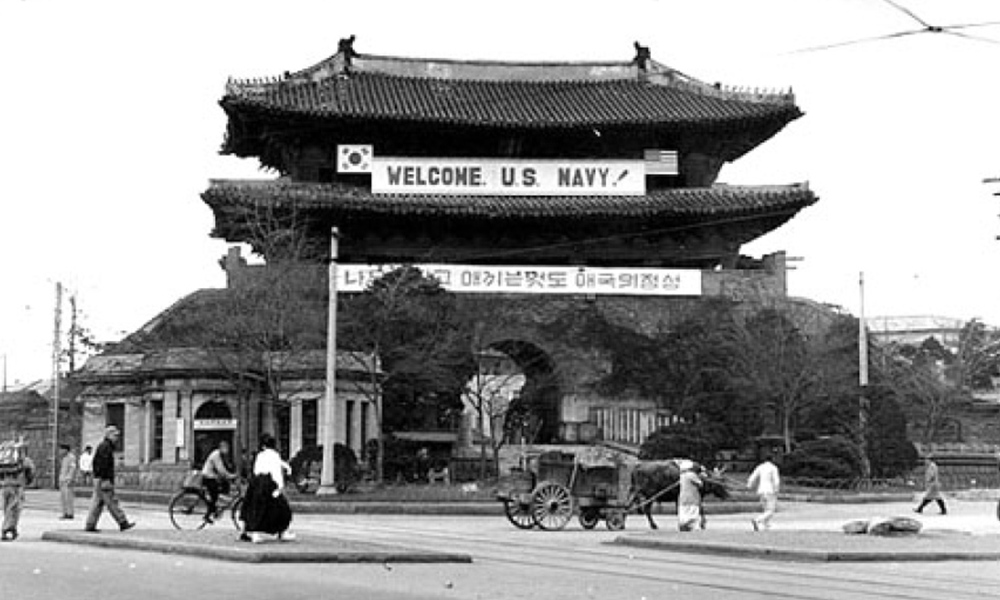

1904年ソウル 南大門

2006年ソウル 南大門

1950年ソウル 南大門

1940年代初ソウル 南大門

TAKAZAWA Yōko

l The establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and challenges.

l Transition to the federal system and agendas.

l The relations between financial issues and a reconciliation: through the lens of victims.

Introduction

Nepal, which used to have a civil war for ten years and transited to the federal system after the war, is now facing a number of problems. After a long-term negotiation, in 2015, the country transited to the federal system and established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[1] However, although two years have passed since the restoration, there are several problems regarding the system. This essay will discuss potential of the federal system within the peace process in Nepal.

The Establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Transition to the Federal System

Since 1996, the Nepal Communist Party, the so-called, ‘Maoist Centre’ had fought the ten-year civil war. They sought to resolve social and economic inequalities. The war was brought about by discontent with social discrimination and inequalities among people from lower caste classes. They aimed to obtain the right of national self-determination and autonomy (Lawoti 2012: 136; Pasipanodya 2008: 378). After the war, the peace accord was signed in 2006. It agreed on a reconciliation, and transitional justice, as well as political, social and economic reform. Especially, the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and transition was welcomed by Nepali society, which had suffered from the war. People believed that the commission would play a significant role in a reconciliation amongst people. Furthermore, the interim constitution of Nepal, which was enacted in 2007, decided to have a transition to the federal system on the basis of identity, as one of resolutions to the long-term identity conflict. The introduction of the federal system to Nepal was welcomed as it would possibly give autonomy to vulnerable people in the society, such as people from the lower caste classes, more autonomy (Lawoti 2012: 149). However, as Buchanan suggested, there was a contradiction between granting autonomy and national sovereignty (Buchanan 1995: 587). There was a big hope for democratization; however, at the same time, discussion about the federal system escalated into a number of protests, resulted in social uncertainty. It also increased hostility amongst people from a different caste class. Pradip Nepal, leader of the Communist Party of Nepal: Unified Marxist-Leninist (CPN-UML), warned that the federal system on the basis of an ethnic group would even cause the civil war (Pandey 2010). Moreover, unstable political climate restricted the development of Nepal, and directly damaged its economy. There had been not that much progress in discussion for seven years. On the 20th of September in 2015, the new constitution was proclaimed, and Nepal became the federal state, which is consisted of seven provinces. However, even today, two years have passed since then, many said that there are a number of problems remaining (Payne and Basnyat 2017). In the new system, political powers are divided into three levels: the federal level, provincial level and local level (The Himalayan Times: 2015). Each level has autonomy and executive power to allocate budget. However, criticism has been increasing that Kathmandu, the capital city of Nepal, maintains its power as central power and it stalled over decentralisation of Nepal as it traditionally did (Payne and Basnyat 2017). There are also voices that a transition to the federal system increases social instability, resulting in weakening the unity of Nepal (Deo 2016).

The Progress of the Reconciliation

Nepal holds a wide range of identity groups. Before its unification in 1769, Nepal was consisted of twenty-two to twenty-four kingdoms and petty states. Even today, there are 92 different languages, and more than 103 caste classes and ethnic groups (Pandey 2010: 40). The caste system was officially abolished in 1963; however, the so-called, Caste or the Jat people, which is based on ethnic identity, still has strong power over a range of aspects in Nepali society today. Bahun and Chhetri are treated as the highest rank of the Caste system, and people belong to lower caste classes are oppressed and are left behind poverty. Social composition has not been changed that much.

As this essay previously mentioned, hostile feeling amongst caste classes and ethnic groups of people has been increased during political and social instability caused by the civil war. Furthermore, the progress of peace process is also not developing well. According to Kriesberg and Rigby, a ‘reconciliation’ can be described as the process of individual group of people, who used to be oppressed each other, aim to coexist (Kriesberg 2001:48; Rigby 2010: 234). In that sense, the meaning of a ‘reconciliation’ in Nepal, which has a range of identity conflicts, could be helpful to stimulate the peace process. However, the foundation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and transition, which used to have high expectation, is seriously delay, and its capacity is limited. Whereas, more than 6,000 cases have been already raised and thus, the committee is facing a number of challenges in order to meet needs of people (Rausch 2017).

Economic Problems and the Reconciliation: The View of Victims

These is also criticism that the peace process is initiated by political elites and legalism, and it is lack of voices of victims (Robins 2009; 2011; 2012). Nepal is said that one of the poorest countries in Asia. Indeed, according to the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, the Grass Domestic Product (GDP) in Nepal is worth 848 US dollars in the year of 2016 and 2017. The country is categorised as the Landlocked Developing Country (LLDC). Pandey argues, ‘Problems of Nepal are not social expulsion but are poverty (original: ネパールの問題は社会における排斥の問題ではなく、貧困である)’ (Pandey 2010: 50). Alongside an issue regarding a budget distribution for the transition to the federal system, economic problems received close attention of Nepali people. The area, which had the fierce civil war, were a poor district. Therefore, most victims seek to have prompt financial support to restore their daily lives rather than to resolve human rights issues, which often received international attention (Robins 2011: 98). However, as this essay previously mentioned, political uncertainty over identity crisis created by the civil war did not resolve economic problems, but even it damaged economy (Bhatta 2012: 3).

On the other hand, a number of aid organisations such as UNDP and the World Bank warn that social inequality has great impact on the process of economy development. Mani argues that economic and social issues should be also considered in the peace process (Mani 2008: 264). Bhatta criticises that vulnerable governance caused by political confrontation in Nepal limited development and reduced investment from the world. It was resulted in curtailing economic activities (Bhatta 2012: 3).

Conclusions

Ten years have passed since the end of the civil war. During the aftermath, identity conflicts became extremely political, while a reconciliation did not have that much progress. There is anxiety that even the federal system accelerates identity conflicts. On the other hand, most people, especially who belong to the lower caste class, seek to resolve economic inequality. Indeed, vulnerable governance, had negative impact on economic activities. There is concern that these problems regarding the peace process fosters frustration of people and worthens further identity conflicts. It could be said that if people believe victim-oriented resolution, they should immediately establish both the federal and reconciliation system and should contribute to the progress of the peace process. It is also important to argue that when people aim to create good governance and try to reach a reconciliation, they should not go toward weakening the unity of the nation, but they must find a way to the coexistence of different identity groups.

Bibliography

Bhatta, Chandra D. 2012. International Policy Analysis: Reflections on Nepal’s Peace Process. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Accessed 21 April 2015. Available at http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/08936-20120228.pdf

Buchanan, Allen. 1995. ‘Secession and Nationalism’ in Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell. 586-96.

Deo, Shambhu. 2016. ‘Identity-based federalism: Decentralisation is a better option’: The Himalayan Times. Accessed 3rd December 2017. Available at https://thehimalayantimes.com/opinion/identity-based-federalism-decentralisation-better-option/

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, The Basic Data: Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal. Available at https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/nepal/data.html

Kriesberg, Lewis. 2001. ‘Changing forms of coexistence’. In Reconciliation, Justice, and Coexistence: Theory and Practice, ed. M. Abu-Nimer. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books.

Lawoti, Mahendra. 2012. ‘Ethnic Politics and the Building of an Inclusive State’, in von Einsiedel S., D. M. Malone and S. Pradhan, eds. Nepal in Transition: From People’s War to Fragile Peace, Cambridge University Press.

Mani, Rama. 2008. ‘Editorial: Dilemmas of Expanding Transitional Justice, or Forging the Nexus between Transitional Justice and Development’. In The International Journal of Transitional Justice Vol. 2: 253-265.

Pandey, Nishchal Nath. 2010. New Nepal: The Fault Lines.: SAGE India.

Pasipanodya, Tafadzwa. 2008. ‘A Deeper Justice: Economic and Social Justice as Transitional Justice in Nepal’. The International Journal of Transitional Justice Vol. 2: 378–397.

Payne, Iain and Basnyat, Binayak. 2017. ‘In Asia – Federal Provisions of Nepal’s Constitution in Jeopardy’: The Asia Foundation. Accessed 3rd December 2017. Available at https://asiafoundation.org/2017/07/26/federal-provisions-nepals-constitution-jeopardy/

Rausch, Colette. 2017. ‘Reconciliation and Transitional Justice in Nepal: A Slow Path’, August 2, 2017, The United States Institute of Peace, Accessed 24th November 2017. Available at https://www.usip.org/publications/2017/08/reconciliation-and-transitional-justice-nepal-slow-path

Rigby, Andrew. 2010. ‘How do post-conflict societies deal with a traumatic past and promote national unity and reconciliation?’ in Peace and Conflict Studies: A Reader, eds. C. P. Weber and J. Johansen. Abingdon: Routledge.

Robins, Simon. 2009. ‘Whose voices? Understanding victims’ needs in transition. Nepali Voices: Perceptions of Truth, Justice, Reconciliation, Reparations and the Transition in Nepal. By the International Centre for Transitional Justice and the Advocacy Forum, March 2008’. Journal of Human Rights Practice 06/2009, Volume 1, Issue 2: 320-331.

Robins, Simon. 2011. ‘Towards Victim-Centred Transitional Justice: Understanding the Needs of Families of the Disappeared in Postconflict Nepal’. The International Journal of Transitional Justice Vol. 5: 75–98.

Robins, Simon. 2012. ‘Transitional Justice as an Elite Discourse: Human Rights Practice: Where the Global Meets the Local in Post-conflict Nepal’. Critical Asian Studies 44-1: 3-30.

The Himalayan Times. 2015. ‘Nepal embarks on journey towards federal destiny’ Accessed 21st December 2017. Available at https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/nepal-embarks-on-journey-towards-federal-destiny/

Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Nepal. Accessed 21st December 2017. Available at http://www.trc.gov.np/

[1] The function and duty of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are as followings:

(Website of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission: http://www.trc.gov.np/about-us)

Provide the victims with identity card as prescribed and also provide them with information after completion of investigation.