1872年東京 日本橋

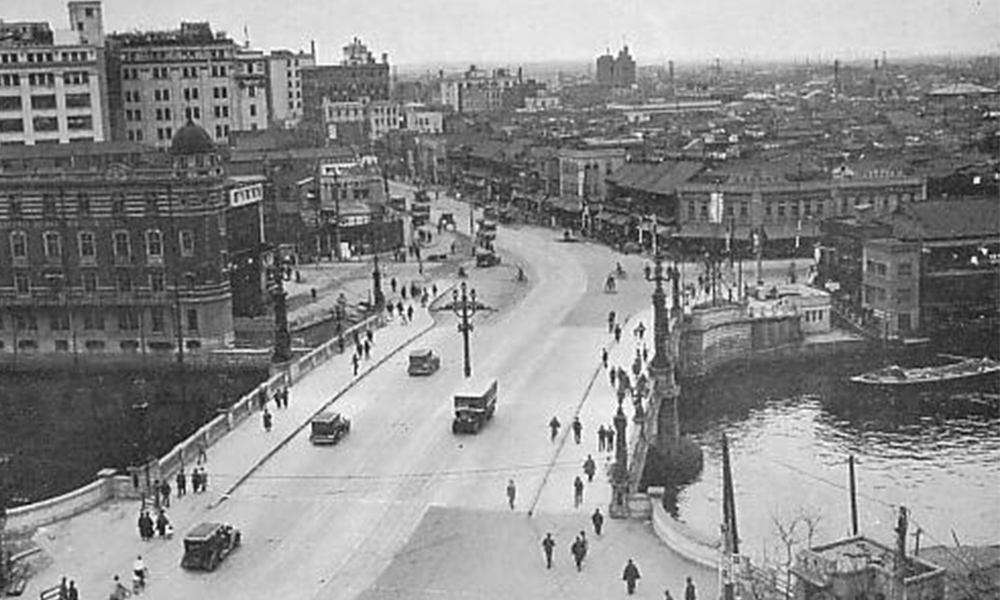

1933年東京 日本橋

1946年東京 日本橋

2017年東京 日本橋

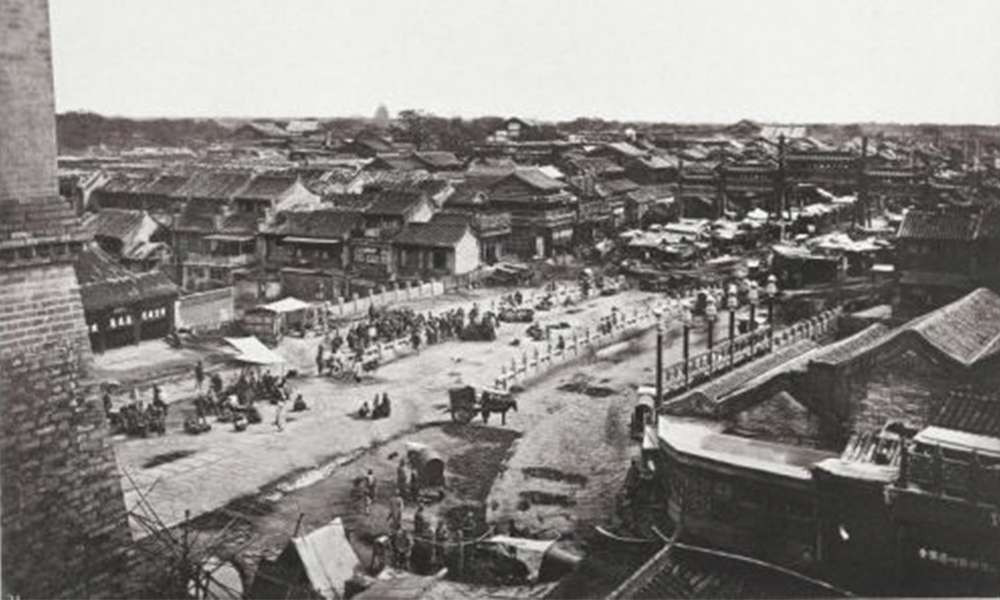

1872年8月〜10月北京 前門

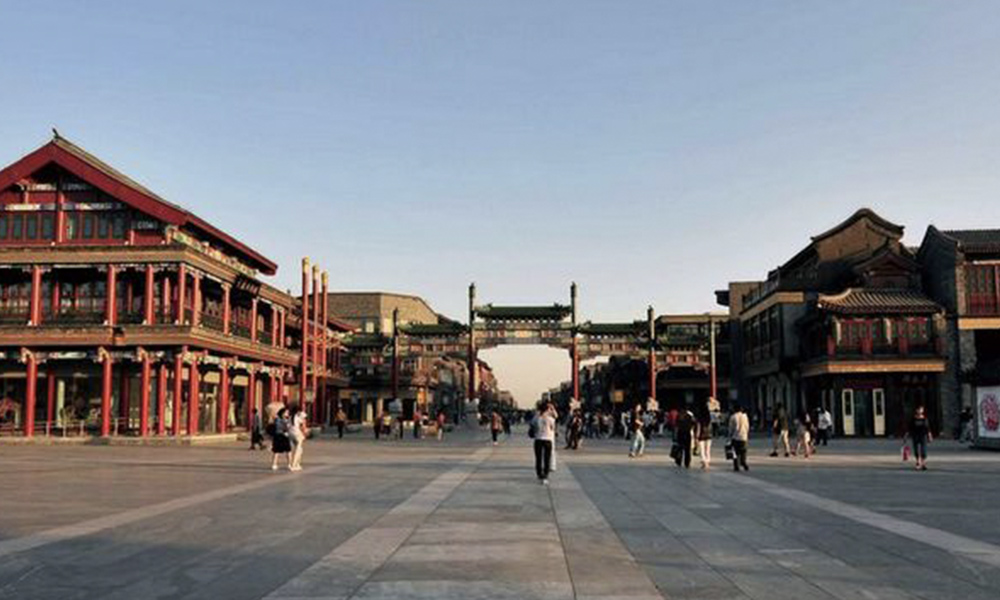

現在北京 前門

1949年前後北京 前門

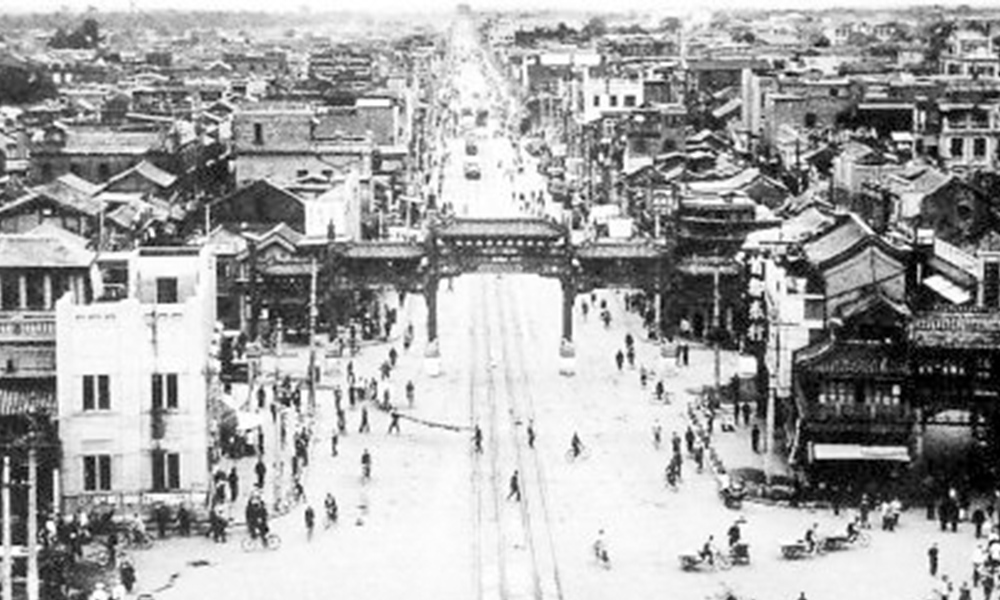

1930年代北京 前門

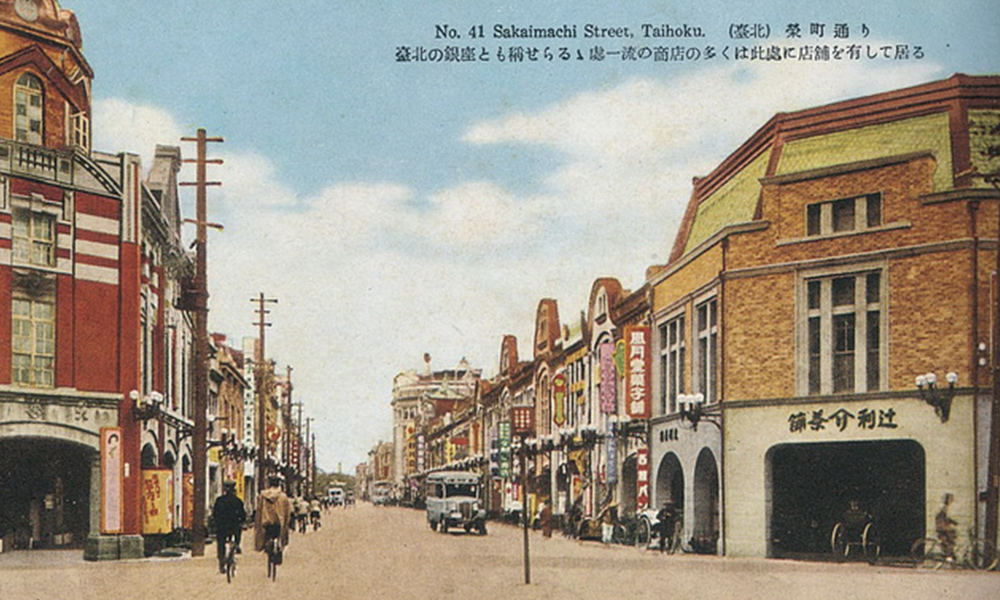

1895年台北 衡陽路

1930年代台北 衡陽路

1960年代台北 衡陽路

現在台北 衡陽路

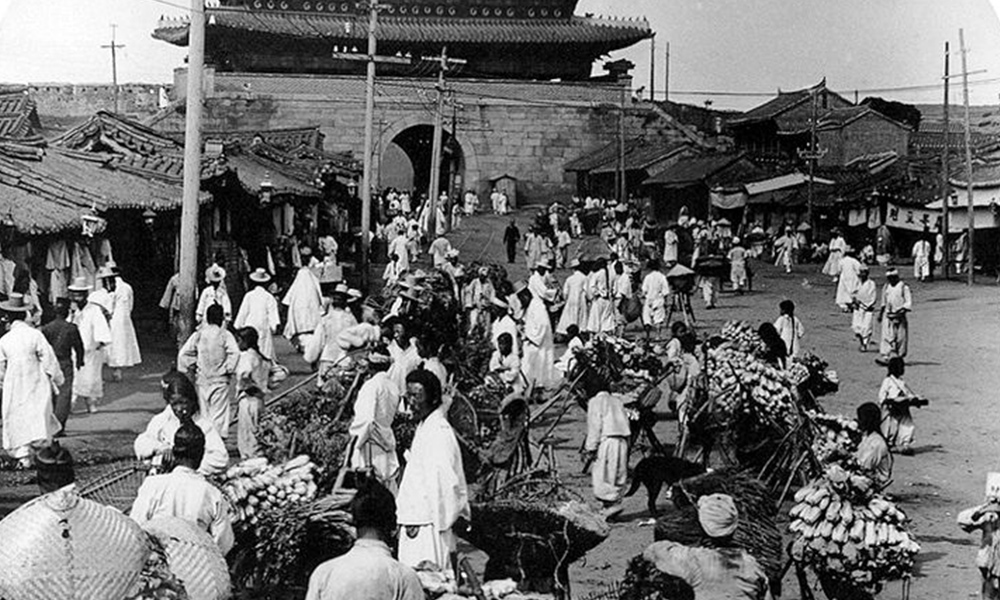

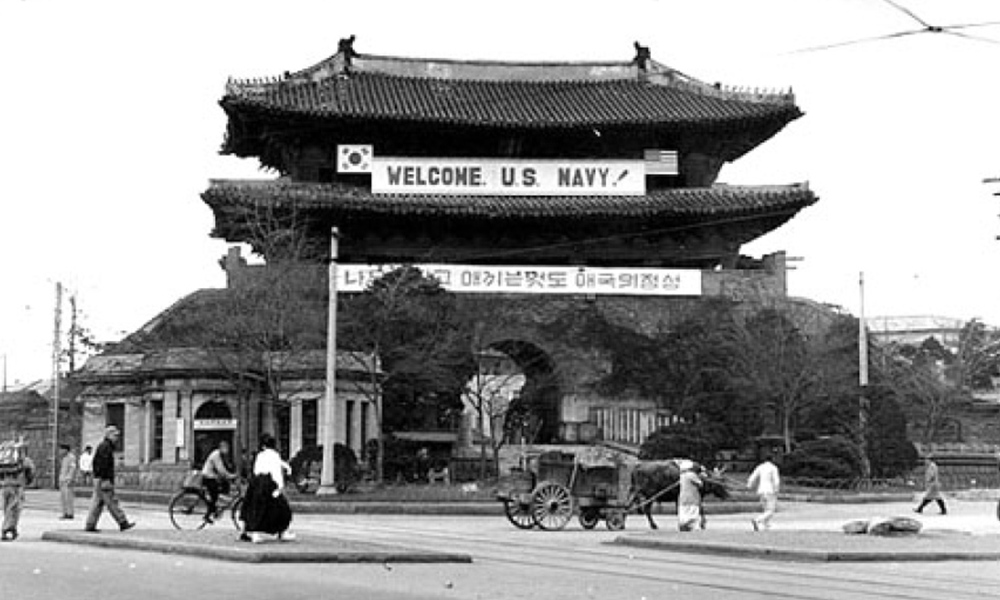

1904年ソウル 南大門

2006年ソウル 南大門

1950年ソウル 南大門

1940年代初ソウル 南大門

This book (Hashimoto Shinya, Kioku no Seiji (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2016), 201, 33) explores the Baltic states and their internal and external challenges- safety, the EU membership issues, and education, language, and citizenship issues including ethnic Russians within the countries. It centres around how these issues intertwine to render history the focal point of politicized disputes. With this, the book unearths their historical backgrounds, the political processes from the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union to the EU membership, the exacerbating relation with Russia after joining the EU, and the developmental processes of historical memory deriving from the Baltic states inside the EU.

The asset of this book, when discussing the issue of historical awareness in East Asia, is in abolishing the simplistic image regarding European history- and memory-related policies, which are simplified and idealized as a model. Through this book, we can observe from the outsiders’ perspective the process in which the historical memory, originating from the Baltic states, fractured the not-easily-restored relation between the EU and Russia as well as the disputes in the midst of conflict resulting from it. The focus of the conflict is the problem of what historical revisionism indicates in the state of politicized history. Furthermore, the author examines how “justice” such as “human rights” and “subversion of fascism” is structurally incorporated and develops by being conscious of comparison. This work thus not only gives suggestions to regional specialists of East Asia, but also to researchers of oral history and people in the field of historical sociology in general.

I, the critic, specialize in Japanese history of political diplomacy and East Asian history of international relations. I was nevertheless appointed as the reviewer of this book. It is likely due to my experience in visiting Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, when the international Slavic conference was held in Sweden in 2010. I made my way to a Russian cemetery in the outskirts of Tallinn with a friend in Russian studies, Sakon Yukimura, to see a monument concerning a ‘commemoration of triumph.’ There, I met a woeful Russian elderly and with Sakon’s interpretation, we inquired the elderly about the arduous conditions of Russian residents after Estonia’s independence. His forlornness and anger echoed with the rage of an English-speaking Estonian elderly, whom we encountered at a history museum, directed at Russians. They were potently burnt into my memory under the summer sun. While being sunk in the deep thought of anger deriving from these individual experiences, I was grateful that this book allowed me to study, based on a theoretical viewpoint and from the comparative perspective of the Baltic states and East Asia, the phenomenon of history and memory floating in the contemporary world as a political issue.

First, I would like to provide a brief overview of this book. The prologue introduces the civil commotion in April 2007 in Estonia over the removal of the statue of a Russian soldier who played an active part in World War II. On the extension of the Revolutions of 1989 and democratization, a fierce political collision is elicited by historical interpretation and memory, and history and memory are politicized and transformed into conflict (p. 18). The book problematizes that this yields a phenomenon that is a “fitting axis of contrast” for Japanese society.

Discussion generally develops chronologically. The book is divided into the following chapters: the first chapter on the background of various historical interpretations; the second chapter on the domestic struggles and international implications over citizenship, civil rights, education, and language of Russian-speaking residents from the time of independence from the Soviets to joining the EU; the third chapter on the structural analysis of nationalism spouting after membership to the EU; and the fourth chapter on the positive analysis of symbolic events hinted by the third chapter.

Chapter 1, “Rekishi ni Umekomareta Funsō” (Conflict buried in history), explores what type of historical phenomenon and the difference in that interpretation the ruptures of historical memory stem from. In other words, it discusses what sort of historical phenomenon a “mine” (p. 19), brimful of social conflict, is buried under as historical interpretation and memory politicize.

The most remarkable incident in which historical interpretation is significantly divided as a “mine” is the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 23, 1939. Stalinism and Nazism are lumped as totalitarianism, and this demonstrates the friction between the nationalistic historical viewpoint emphasizing “hero[ic]” resistance under the occupation and Russia’s historical perspective taking the stance that it was inevitable in order to delay the Nazi attack (Beyond Chapter 2, this friction intertwines with internal and external factual problems and leads to an analysis that is substantially structured by political problematization).

The second mine involves the interpretation of the treaty in which Russia recognized the Baltic independence. What prompted the independence of the Baltic countries was the surrender of the western regions to Germany upon the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This was achieved in the midst of the following states: the declaration of independence executed by national heroes before another invasion by the Red Army; fighting the groups that were plotting the establishment of the Bolshevik regime while receiving help from Great Britain and the military volunteers of Finland, which invaded amidst the counter-revolutionary war; and being in disorder with the groups scheming various nation formations under Germany’s protection (p. 34-5). Estonia was the first to attain independence upon the Treaty of Tartu with the Soviet Government in February 1920. Accordingly, Russia recognized the independence of Lithuania in July and Latvia in the subsequent month. On the other hand, the Allies delayed the recognition of independence despite advocating the principle of self-determination. Under the Medvedev regime in Russia, there existed influential historians who asserted that “the separation from the Russian Empire carries no legitimacy and it is nothing more than a temporary territorial loss as a result of civil war and revolution.” I hear that this is affecting the problem of the Estonian boarder yet being unsettled and the implication behind the 1939 agreement.

Chapter 2, “Haijoka, Tōgōka, Dōkaka” (Is it elimination, integration, or assimilation?), centers around the developmental process of the democratization movement in cooperation with foreign groups and the following treatment of ethnic Russians. The former involves forced deportees from the Baltic states who repatriated from Siberia after Gorbachev’s appearance in 1985.

The Baltic states became independent upon the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It was, however, insurmountable to entirely banish ethnic Russians in order to gain membership to the EU after democratization. In the democratization process, the conclusion of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on August 23rd gave birth to “the Baltic Chain.” Moreover, the validity of the Treaty of Tartu, which recognized independence after World War I, was disputed. They suggest that democratization and the binding process of historical memory existed early on. “The re-examination of the past directly [became] the nucleus of political strife in real life.”

Additionally, tension built up in the country over the issue encompassing civil rights and citizenship, education, and language of Russian-speaking residents amidst the EU membership problem and under pressure from Russia. Owing to the high percentage of Russians in Latvia, citizenship was granted by the idea of multicultural nation formation. In contrast, the citizenship law, which dextrously eliminated ethnic Russians, in Estonia was executed in a way that the EU only inevitably accepted. The basis of argument for this was a historical framework that “notwithstanding the efficacy of independence by the Treaty of Tartu, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact commenced unjust occupation, which continued until the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The dissolution accordingly ‘restored’ independence.” It thereupon gave rise to the logic that whereas Russian-speaking residents who lived in Estonia prior to 1940 were granted citizenship, those who flowed in during the period of the unjust ‘occupation’ could not be approved. This logic was utilized against the EU, which sought pluralist integration under multiculturalism, to legitimize Estonia’s citizenship law that substantively displaced a great many Russians (p. 69).

In other words, the historical interpretation of whether independence was “restored” following the dissolution of the Soviet Union or it was newly realized brought a significant change to the residents’ citizenship. What is more, the book also points out the possibility that this citizenship policy interweaves with the intent of removing ethnic Russians in the re-privatization process from socialism (p. 79) and the presence of the motive from the Russian side in wishing to reserve the Russian citizenship (p.81). This is an intriguing point that entwines with my last thought.

Chapter 3, “‘Kioku no Sensō:’ Rekishi to Kioku wo Meguru Seiji to Funsō” (“War memory:” politics and conflict over history and memory), takes up the developmental process of phenomena that expresses the national emotions brought out by the politicization of history. This took place in accordance with the approval of Estonia’s and Latvia’s membership to the EU in May 2004 and the subsequent ethnic Russian problem the local government was fully entrusted with. When the Bronze Night (the public disturbance (1 dead, 150 injured) surrounding the removal of the statue honoring a Red Army soldier who died in the reoccupation/liberation (I am one critic who wrote entirely contrastive common names) of German-occupied Estonia by the Soviets in the last stage of World War II) occurred in Tallinn in April 2007, it exposed the discrepancy in the understanding of security within expanded Europe, and its relation with Russia became tense (p.102). Four distinct historical images are introduced in the background of the bloody incident over the historical problem in independent Estonia, attained by the peaceful democratic revolution.

The first and fourth stem from the battle between fascism and democracy during World War II and the propaganda by the Allies that gave meaning to World War II. They both share the same turning point at 1945. The first involves Western European memory that values freedom and democracy reinforced by the memory of resistance from the residents’ viewpoint. The fourth emphasizes the Soviets’ heroic battle during the anti-fascist war called the historical view of “the Great Patriotic War” and expressly distinguishes Stalinism from fascism.

In contrast, the historical viewpoints of the second and third can be regarded as the Central Europe type, as they both place history’s turning point at 1939, the start of the occupation by totalitarianism in the aftermath of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (The second has its historical viewpoint originally centred around Jewish people, and 1945 is also the turning point). As opposed to the former that emphasizes human rights norms, the latter stresses national identity. This is where they differ in their historical viewpoints (as understood by the critic, p. 103). In other words, the second establishes infringement of human rights, symbolized by the massacre of Jewish people, as an axis. It is therefore a historical view that expands to the repression of freedom and forced deportation of residents by the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe following the war, and emphasizes the norm called human rights. The third accepts the same issue as a nation’s hardship. It is thus a historical viewpoint that problematizes the cooperation of vs. the Soviets and vs. the Nazis while regarding Stalinism in the same light as fascism.

Primarily, the third historical awareness works as a driving force and as it passed intense friction with the fourth, collaborators inside the Soviet regime and criminals sealed under it were convicted after independence. It is the fourth chapter that focuses on it and could thus be considered a case study of conviction.

There was a man named Vassili Kononov who, while engaging in partisan activities under the Nazi occupation, killed a civilian who collaborated with the Nazis. The fourth chapter takes up his war crime trial and states the catalyst of the conflict, developmental process, and conclusion. It discusses how the mine of historical phenomena functions and explodes alongside the Kononov’s incident. The trial progressed to determine whether the incident was a war act amidst the anti-fascist war or a murder. The actual issue was whether the killed collaborator was a civilian or soldier and whether Kononov was qualified to attack in the first place. Consequently, he was pledged guilty as a war criminal by both the national and international court of Latvia. However, Russia, a supporter of Kononov, stiffly opposed it and accelerated a movement to applaud him as a “hero of partisans.”

I would like to summarize my thoughts and comments below. The first point I would like to make is the following: when comparing decolonization from the Japanese empire in East Asia to the Baltic independence from the Soviet Union, there was a clear correlation between the former, which carried out the thorough forced deportation of residents in the former suzerain state, and the latter, where the same thing did not occur due to the confrontation of human rights norms and pressure to join the EU. In the latter, as the new wall was constructed by the residents with the mobilization of history, it intertwined with privatization, brought out by de-socialism, and accelerated the residents’ nationalism. On the other hand, the protection of human rights norms and construction of pluralistic society were a must to join the EU. For neighboring Russia to protect the Russian-speaking ethnic group, a significant restriction was imposed on the nationalism of the Baltic countries. This was truly a contrastive point to East Asia which lost its influence on the surroundings under the occupation of Japan as a former suzerain state. However, the phenomena in the Baltic states may actually be the same phenomena that we, in East Asia, are facing in a different topology as a transborder problem of historical awareness.

One historical view takes the stance of affinity to the nationalism of local residents that sets resistance, to the uninterrupted occupation by totalitarianism, as a core (the aforementioned third viewpoint). The historical viewpoint of the Great Patriotic War by Russian-speaking residents (the fourth one) collides intensely with this third historical view internally. “Society where ruptured memories coexist and compete” (p. 117) is where the two distinct historical views cannot be compatible. This is the Baltic states today. From the historical viewpoint of the former, people in Estonia “carved into their hearts the purges and forced immigration to Siberia under Stalin’s regime, exile to Sweden, and grievous experiences under the prolonged Soviet regime. People then entrusted these memories with the word, ‘occupation’” (p. 114). This is the description of Estonian society. On the contrary, the latter places ethnic Russians as “people who flowed in as soldiers and laborers from each Soviet region and remained after the restoration of independence. They were thereby pushed to the stateless environment” as a result of “liberation” and victory attained by immense sacrifices. Either one is recognized as history’s victims by the parties concerned. However, we cannot pay our respects to their memories. This is the state that symbolically demonstrates the conflicting structure of historical recognition between Japan and Korea.

A clue to overcoming such a conflicting structure is perhaps to deepen research on nationalism, the one sought by international collaborative research. This is my second thought. Regarding the emphasis on the existence of victim nationalism that stresses the memories of victims surrounding “loss” such as deportation, dispersion, and oppression (p.117-120), this has a point of contact with historical conflicts in East Asia. In order to examine it deeply, we may revert to the results of nationalism research and establish an analytical framework about the origin of nation by, for instance, setting a primordial or methodical one as an axis. Would it then be possible to compare by genuine means and arrive at new knowledge? As if to respond to such an expectation of the critic, the author abundantly provides such materials.

There were Estonian and Latvian soldiers who continued resistance, even after the re-occupation by the Soviets, by joining the battle on the German side. One example is the collusion process of the aforementioned frameworks of the third and fourth historical awareness over the question of whether the act of these soldiers could be regarded as “heroic resistance.” Have the readers noticed that the experiences of the occupied and the image of heroic resistance are perceived by dating back to the Crusade in the North in the far medieval period (p. 27)? Did the tribal society of so-called Estonia exist first or did people, who were obstructed by the industrialization of advanced areas in the West of the Russian Empire (p. 29), artificially produce memories? The relationship between the presence of nation and historical memory is once again questioned throughout the book. Evoking resistance as the image of national autonomy highly correlates with how South Korea’s nationalism took the invasions by the neighboring countries as a chance and dedicated the Righteous Army and rebellion as the nucleus of national autonomy. The great powers such as Sweden, Dane, the Republic of Poland (The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and later, a republic), Russia, and Germany invaded the Baltic regions from the surroundings, and the regions became the state of disorder since the 12th century. I believe the problem of what type of substratum society sustained war until today suggests the possibility of Japanese-European comparison to feudalism research pursued by Asakawa Kan’ichi at Yale University in the first half of the twentieth century.

The second is the reconciliation problem following democratization. During my master’s, I have directly witnessed on the TV screen the groups of people who had been subjected to the deprivation of their ‘selves’ and their process of transformation into collective bodies. They were the following: the 1986 Philippine Revolution, South Korea’s struggle for democracy in 1987, the Revolutions of 1989 and the Tiananmen Square protests, and the democratization strife in 1991 Taiwan (this did not appear on live TV). Before democracy, people who were usurped of ‘selves’ and placed “under occupation” or authoritarian regimes told the past oppressions and injustices with all their strengths. Their excitements in socially raising questions were burned into my memory. It has been thirty years since then, and I was able to learn through this book the internal and external developments of intense discord over historical memories not only in East Asia but in the Baltic countries. What is more, I was able to realize once again that the process of democratization has not ended, that I still exist on the extension of the major events in international politics during my younger days, and that I have subconsciously continued my thought in the surge of democratization.

Upon understanding this, however, I would like to know how attempts at reconciliation not only with the citizenships and properties of Russian residents but also with the whole of Russian citizens developed. How did the dialogues between intellectuals about the removal of the political mines develop? The texts also refer to the writing of both arguments as a result of failure or to a part of inconsistent declarations. Finally, “global denunciation for the crimes under the totalitarianistic communist regime” was resolved by the decision of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 2006. “Infringement on human rights” and “sympathy, understanding, and approval of crime victims” were resolved as a result, and the Vilnius Declaration was approved at the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 2009. The author also points out the birth of “a fracture which is difficult to restore” between Russia and Europe upon these resolutions (p. 131).

However, why did the national identity of Russia and these declarations collide? Regarding this, the Russian side set up “the commission of the president of the Russian Federation to oppose attempts at historical distortions that would damage the national interests” and Putin, after being appointed as the chairman, “completely subordinated” history to the nation’s intent. As an extension of that, “the Society of Russian History” was established in 2015 and Russia has been attempting “the reorganization of historical narratives resembling national policy” and legislation that would impact historical memories. The author reports these in detail (p. 135). The epilogue extends its field of view to the phenomena where the politicization of historical and memory conflicts is vibrating sympathetically in the Baltic countries and East Asia (p. 191). However, isn’t this the result of failure in activities aimed at reconciliation immediately after the Cold War? Collaborative historical research in Germany and Poland, while holding various frictions in reality, tends to be united and understood as an “inspiring story.” Why was an inspiring story not made in contrast? I sufficiently understand that attempting to inspect its reasons is why I introduced the book here. The Baltic side requested to review the “past injustices” by penetrating the unrefined, boundless “stark dialogues” to draw the conclusion mentioned in the texts. Because the author’s analyses are so splendid, is it extravagant of me to wish to know more about the origin of “emotional repulsion” toward this request? I cannot help but think that nationalism wrapped in Estonia’s human rights called justice and its act that in turn stimulated Russia’s nationalism resembles the conditions of East Asia. Isn’t the slogan called “anti-fascism” vibrating sympathetically but also lopsidedly (p. 191)? At any rate, I would like to sincerely thank the author as well as everyone involved for letting me learn immensely.

Asano Toyomi