1872年東京 日本橋

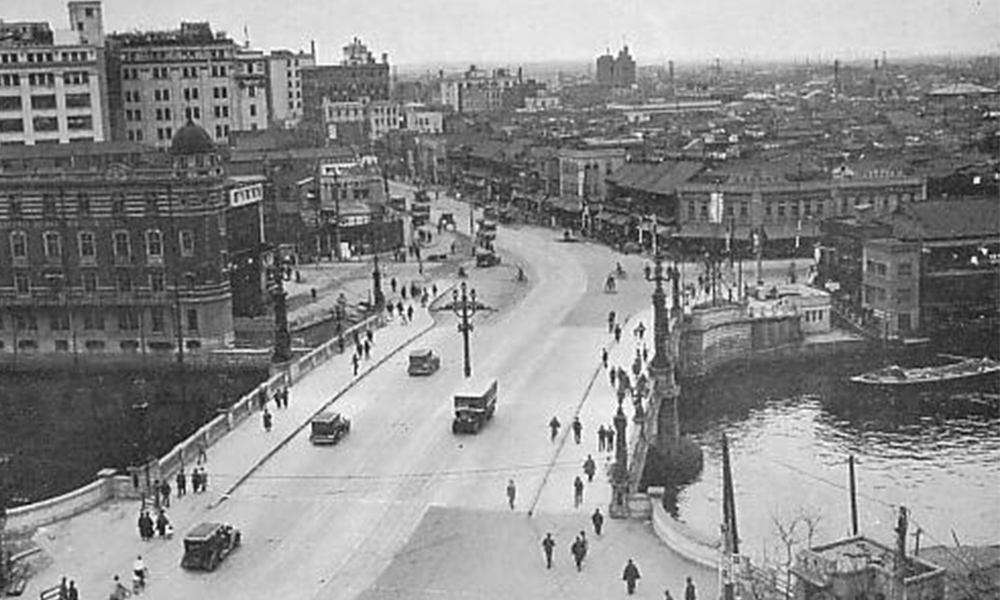

1933年東京 日本橋

1946年東京 日本橋

2017年東京 日本橋

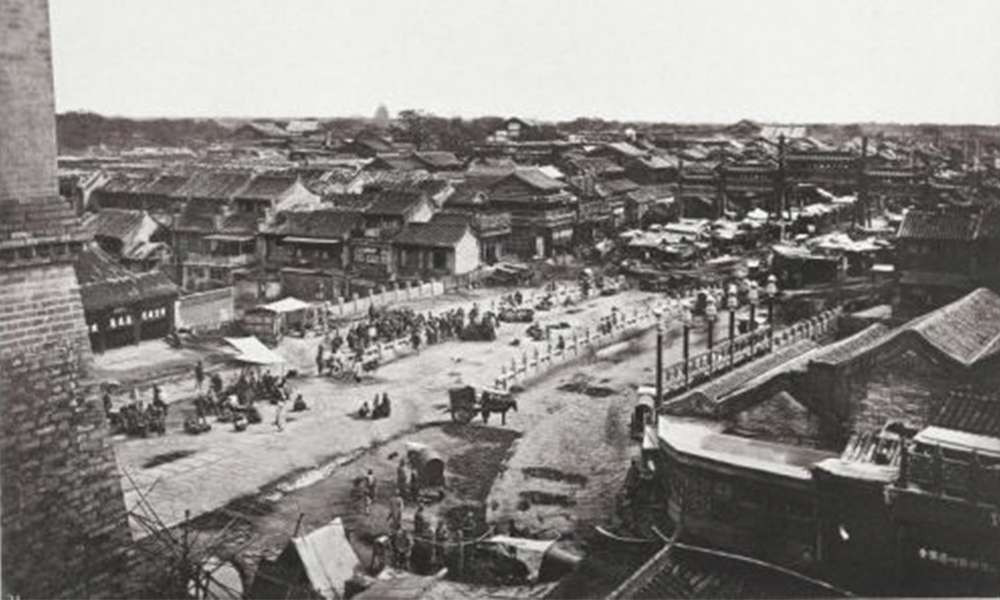

1872年8月〜10月北京 前門

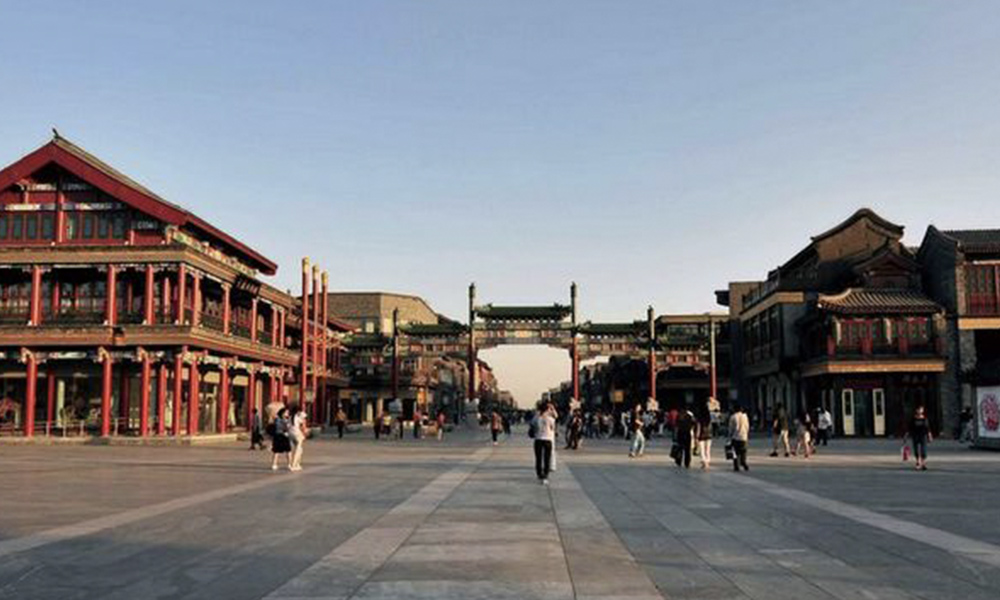

現在北京 前門

1949年前後北京 前門

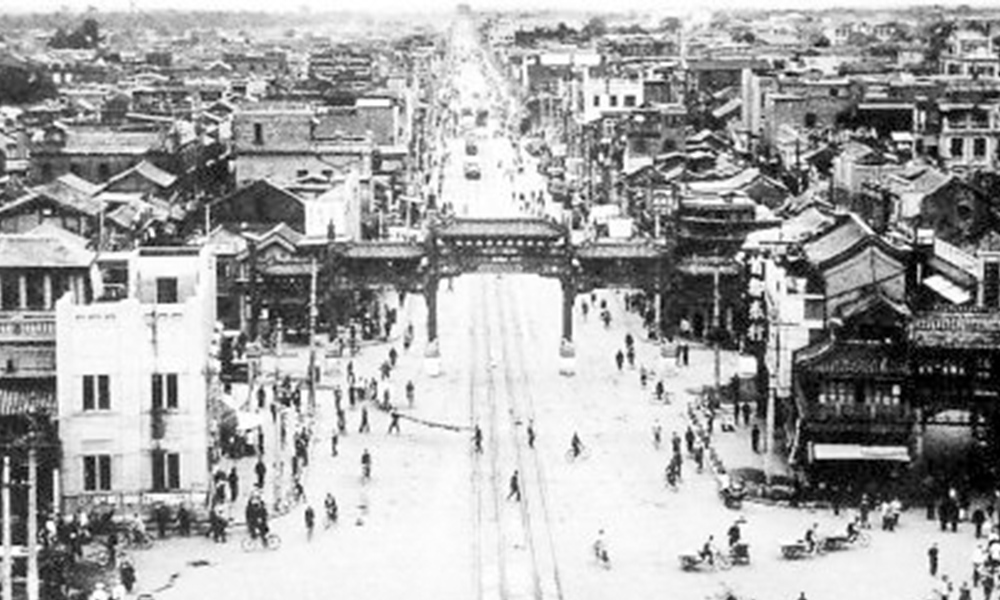

1930年代北京 前門

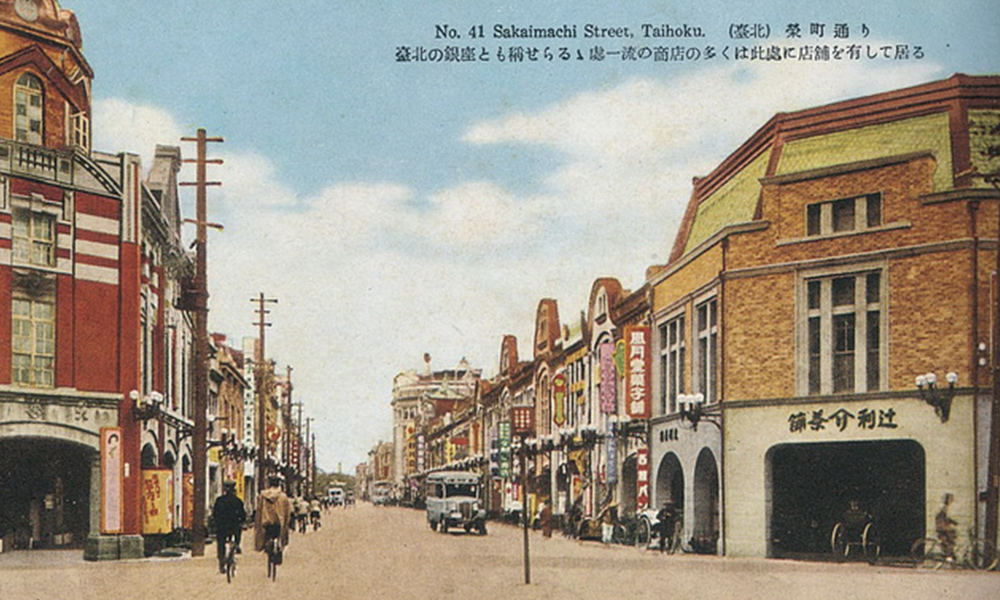

1895年台北 衡陽路

1930年代台北 衡陽路

1960年代台北 衡陽路

現在台北 衡陽路

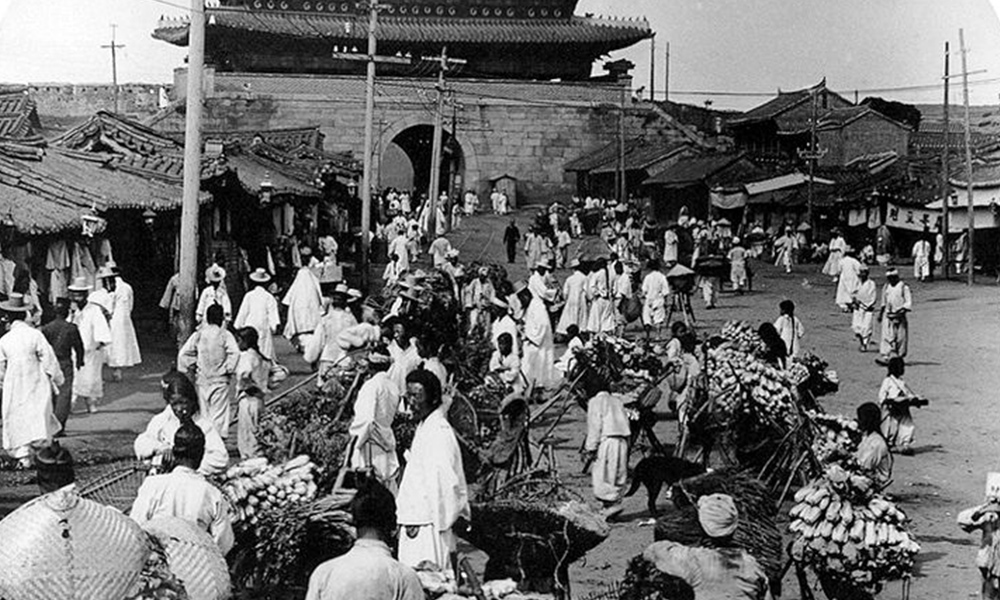

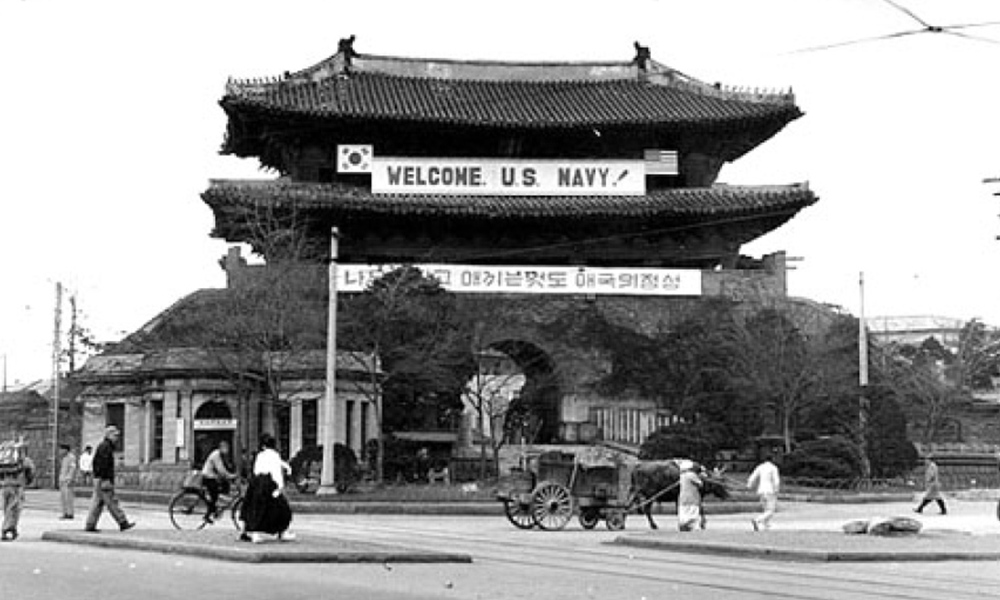

1904年ソウル 南大門

2006年ソウル 南大門

1950年ソウル 南大門

1940年代初ソウル 南大門

NAGAO RYUICHI

A young samurai living in the capital had difficulty with the downfall of the master’s house. He parted from his wife to serve the daimyo of a distant land. To make his way in life, he married a daughter from a respectable family. The new wife was, however, cruel and selfish. The samurai realized he was still in love with the first wife and suffered from a guilty conscience. As he finished his mission, he took the new wife back to her parents and hurried back to the capital. The house was in the state of disrepair and there was no sign of anyone living there, but a light leaked from the wife’s living room. He opened the door and saw his wife sewing in the shadow of a paper-framed lamp. She was young, beautiful, and exactly as he remembered her. He begged her for forgiveness and said, “Let’s live together from now on.” They talked until dawn. He had a short sleep and woke up. There was a women’s corpse lying next to him on the dilapidated floor. It was his wife.

This is a synopsis of the Reconciliation “retold” in English by Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) as a source from Tales of Times Now Past. It is a typical example of “internal reconciliation” that depicts the remorse, apology, and forgiveness of sinners. This only developed within the subjectivity of wishful thinking of self-centered men (just as Pinkerton in Madame Butterfly) and we do not know if the dead wife indeed “forgave” him (There is also a view that Hearn believed that the ghost from the other world actually came to see him).

This is an example of reconciliation between moral non-counterparts over “one apologizes and the other forgives.” There is also a ritual of dogeza, meaning kneeling on the ground, (recently) and responsible persons bowing in a row on the TV as a symbolic act of apology that does not necessarily concur with internal repentance.

A recent example of “reconciliation by apology” is an apology by the Shogi Association toward Miura Hiroyuki, a 9-dan player. The Shogi Association suspended Miura from appearing in official games including the Ryūō match by an insufficient investigation based on the accusation he used Shogi software without authorization. The third-party panel, which was formed before long, approved that “there is no evidence that suffices the acknowledgement of cheating.” The president, Tanigawa Kōji, followed by several responsible persons in the Shogi Association resigned. The newly appointed president, Satō Yasumitsu, apologized to Miura, reconciled with him, and paid the indemnity. The prosecutor and the Ryūō title holder, Watanabe Akira, also personally apologized to Miura.

Today in westernized Japan, a ritual of reconciliation between counterparts often takes the form of a “handshake.” Among yakuza, however, there is teuchi or tejime, meaning rhythmic handclapping in a brief explanation of the terms. This is an old custom dating back to見大人所敬、但搏手以當、脆拝 daijin wo mi uyamau tokoro wa tada hakushushi motte masani kihai subeshi in Gishiwa Jinden. This means to clap hands to express respect when meeting a nobleman and that one must bow courteously by placing both knees on the ground. Moreover, misogi stems from the word misosogi, which is an act of cleansing one’s impurity (kegare) with water. This also symbolizes reconciliation where people involved in the confrontation both take part in misogi and wash away their grudges and vengeful thoughts.

Requesting a reconciliation over conflict between the counterparts implies a motive of avoiding a cost of conflict. The more unfavorable the war situation and the more delayed the ceasefire, the bigger the loss. Requesting a ceasefire by claiming, “Needs must when the devil drives” causes an excessive cost. If the conflict is a pursuit of justice by the subjectivity of the people concerned, avoiding ichiokugyosai, meaning all citizens must choose death before dishonor in a mainland battle, to prioritize the consideration of cost over justice is utilitarianism regarded by Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) with hostility.

He stated that “justice must quite if it sells itself for the cost of something” and that the dissolution of a country must only occur after executing the last murderer (“The Metaphysics of Morals” in Sekai no Meicho Kanto, trans. Katō Shinpei and Mishima Yoshiomi, 474-6). Kant’s justice resembles a retributive punishment of equal retaliation.

A novel by Rudolf von Jhering (1819-1892), Der Kampf ums Recht (1872), exactly negates the idea of “cost of conflict” by describing an episode of an English continental traveler. When his change was stolen at the inn, he extended his stay to restore the damage by bearing the cost which was several times larger than the amount of money stolen. For him, the indemnity was a problem of “Recht” (right, law, and justice) and not that of calculation.

One interesting aspect of this story is the confrontation of consciousness of law between fundamentalism, which is in line with Kant’s justice to “accomplish justice even if it means to ignore the cost,” and utilitarianism, which resembles Jeremy Bentham (1784-1832) who subordinated justice to utility. If anything, the action of the English gentleman is Kant- or German-like, and the German public who ridiculed him seems rather British. Or it may be the difference between the consciousness of law of the Western aristocrat crossing the border and that of the Western commoners.

Regarding the external forms of action such as dogeza or a handshake for reconciliation, it is difficult to balance the hatred accumulated on the inside. There is a risk for the vengeful thought, once supressed, to blow out eventually. For this, a country might issue the “order of forgetting.” The Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, which stretched over one generation, ended in 403 B.C. This war was accompanied by internal discord, and “Do not retrieve the evil” (me mnesikakein) was promised for the reconciliation of both powers (Xenophon, Hellenika, II, iv, 43; Aristotle, Athenian Constitution XXXIX, vi).

In 1660, the throne was restored after the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the English parliament enacted the Indemnity and Oblivion Act. It (excluding some exceptions) decided that injustices [during the wars] “should be forgotten.” This legislation took effect upon the approval by Charles II (1630-85) who turned to the reconciliation policy by tolerance.

After WWII, one of the people who excavated the order of forgetting with the advocacy of reconciliation from history was Carl Schmitt (1888-1985) (“Amnestie, oder die Kraft des Vergessens” (1949), Staat, Großraum, Nomos, 1995, 218-9(Amnestie is the negative form of memory (mnemos)). The general impression was “Schmit, who waved the flag of the Eastern Europe invasion and antisemitism during the Nazi period, is asking too much by requesting ‘forgetting’ after defeat.”

Mass psychology during a conflict is called gashinshōtan, meaning one must tolerate suffering to achieve vengeance, of “the Tripartite Intervention,” “the Memorial Day of National Humiliation” of “the Twenty-One Demands,” and “Remember Pearl Harbor” of the Japan-US war. “Do not forget it” is rather the general slogan. It is difficult to inhibit grudges or vengeful thoughts behind the sense of national justice by law. This itself is the core of ethnic and national identity, especially in international society.

One of the biggest threats to international peace is the restoration movement of “terra irredenta” (unrestored territory). When I go through the entry of “irredentism” alphabetically in English Wikipedia (outside the parentheses are the countries in claim and inside the parentheses are the subject areas), it goes in the order of the following until it reaches a Z: Afghanistan (a part of Pakistan), Albania (a part of Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Greece), Argentina (the Falkland Islands of England), Armenia (a part of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Iran), Austria (South Tyrol), Belarus (a part of Poland, Lithuania, and Russia), Azerbaijan (a part of Iran), Bolivia (a part of Chile and Brazil), Bosnia & Herzegovina (a part of Montenegro and Serbia), Bulgaria (a part of Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Greece, Turkey, and Albania). Japan and its request of the four northern islands is also on the list. These are the dormant volcanos of international conflicts.

What is important to reconciliation is the attitude of the third party. By a young man leaving one farming village for the city, he sees the style of farming village-like thinking and action, which he used to feel was self-evidently absolute, far from a distance (distanzieren). He is then able to subsume the past perspective (Perspektive) under a broader perspective. Karl Mannheim (1893-1947) asserted that this was the first step toward the sociology of knowledge (“Wissenssoziologie”, Handwörterbuch der Soziologie, 1931, 666).

He stated that, in contrast to the general public whose perspective was confined to a specific place like a tree, “the free-floating intellectual class” (freischwebende Intelligenz) that unified various perspectives while flying from a tree to a tree like birds was the bearer of the sociology of knowledge (Ideologie und Utopie, 1929, 135).

Putting the scholarly theories aside, by standing in a perspective that subsumes the perspectives of the people involved in a conflict, the third party in the neutral position to integrate them fulfills the role of this intellectual class. They give advice to the both parties from that perspective, can give them a warning, and moreover, they can serve the function of an arbitrator for reconciliation as practitioners. International organizations such as the League of Nations and the United Nations institutionalize the role of this third party for reconciliation.

Japan that fought Germany-Austria, which was as an ally of Great Britain, America, and France in WWI, battled against Great Britain, America, and France by having Germany-Austria as an ally in WWII twenty years later. This was because it could not receive the support of the three countries for the Japan-China conflict. The reasons that this enemy-ally inversion did not only fail to receive the support of foreign countries, but also that of many Japanese people is known to be due to the assassinations of many Japanese in the upper strata by terrorism and because of the reconversion of the enemy-ally position in postwar Japan that advanced smoothly (Even then, the reason the conversion toward Germany was concluded was because the general public was taken by the climate of “Shōwa Populism”).

The number of dead soldiers in WWI mounted to 16 million and 50 to 80 million in WWII. The number of deaths in wars and civil wars today are said to be several hundreds of thousands every year, and these are once again accumulating hatred and grudges. There are apparently religious groups that hoist the slogan of “universal reconciliation” under these circumstances. What people of the worldly type, who are like authors for the present, think are the following: to encourage peaceful passion such as “fear of death,” “desire to seek necessities for pleasant lives,” and “hope to acquire that by labor” raised by Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) as passions to elicit humanity from the place of struggles and to encourage self-control and tolerance that calmly reconsider mutual differences by supressing “self-deceptive pride” (vain glory) that Hobbes raised as struggling passions. Isn’t the spirit of “tolerance and endurance” once hoisted by a Japanese politician a slogan to guide human history to reconciliation?