1872年東京 日本橋

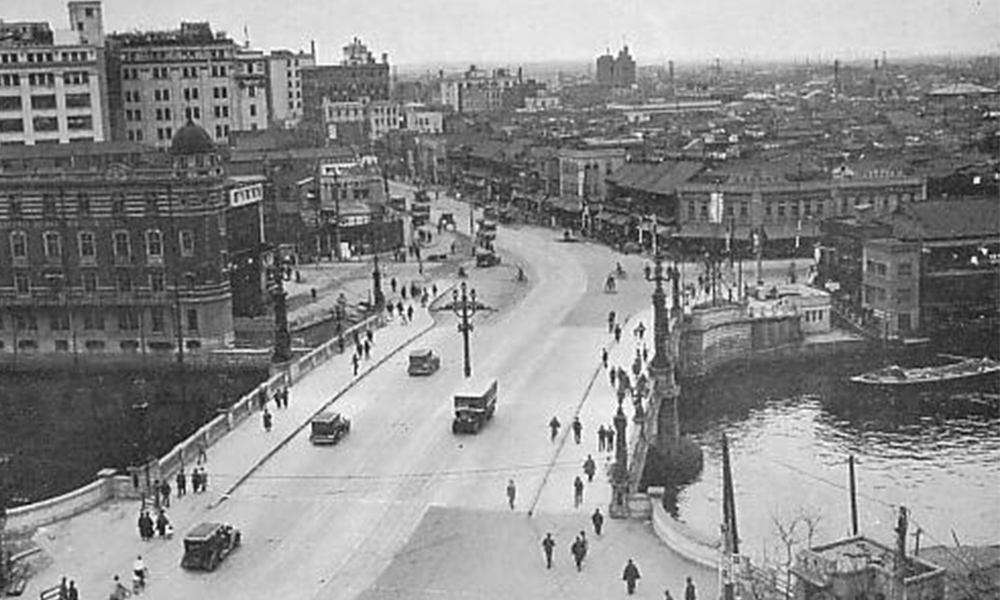

1933年東京 日本橋

1946年東京 日本橋

2017年東京 日本橋

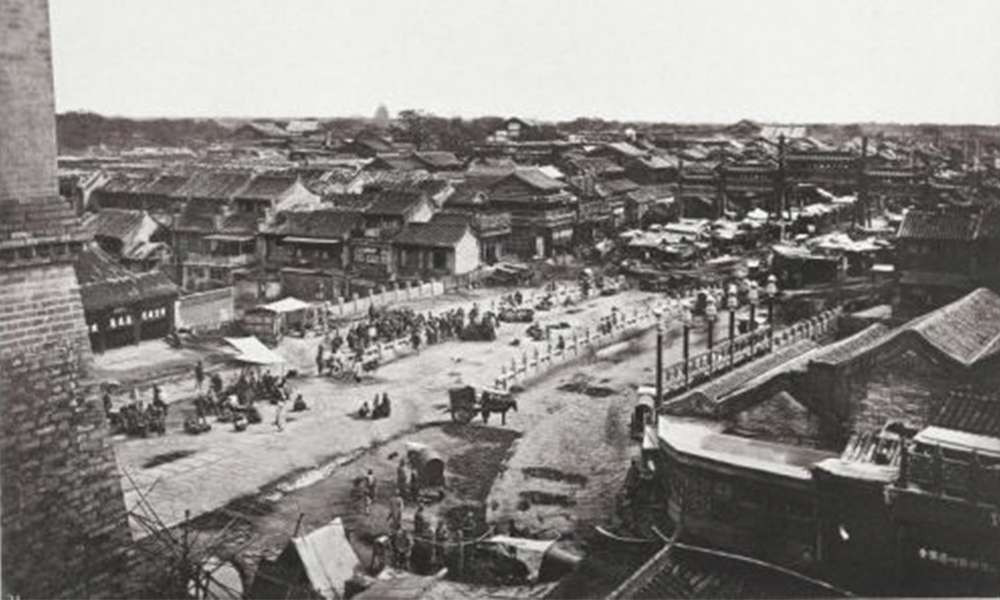

1872年8月〜10月北京 前門

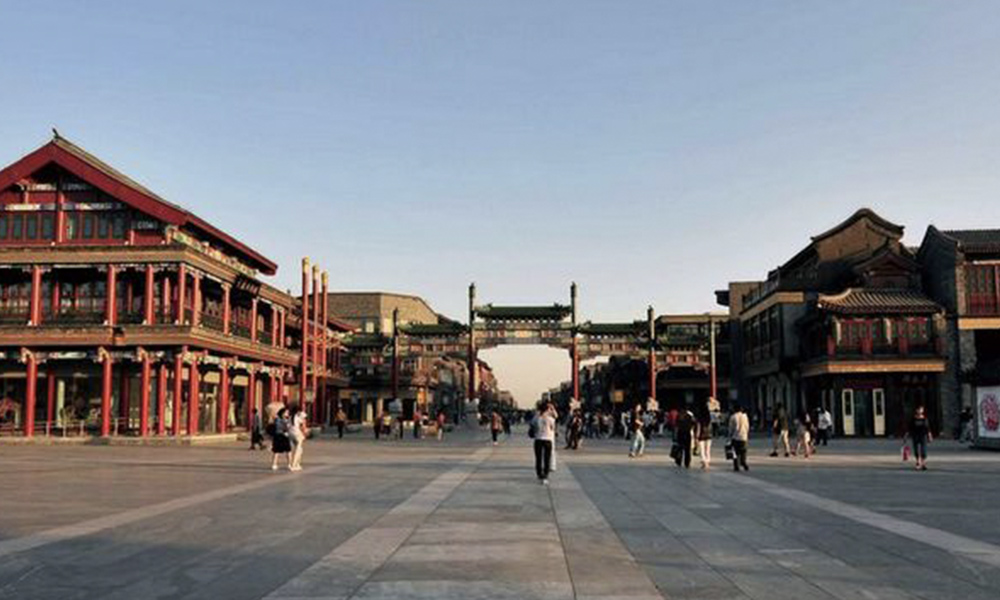

現在北京 前門

1949年前後北京 前門

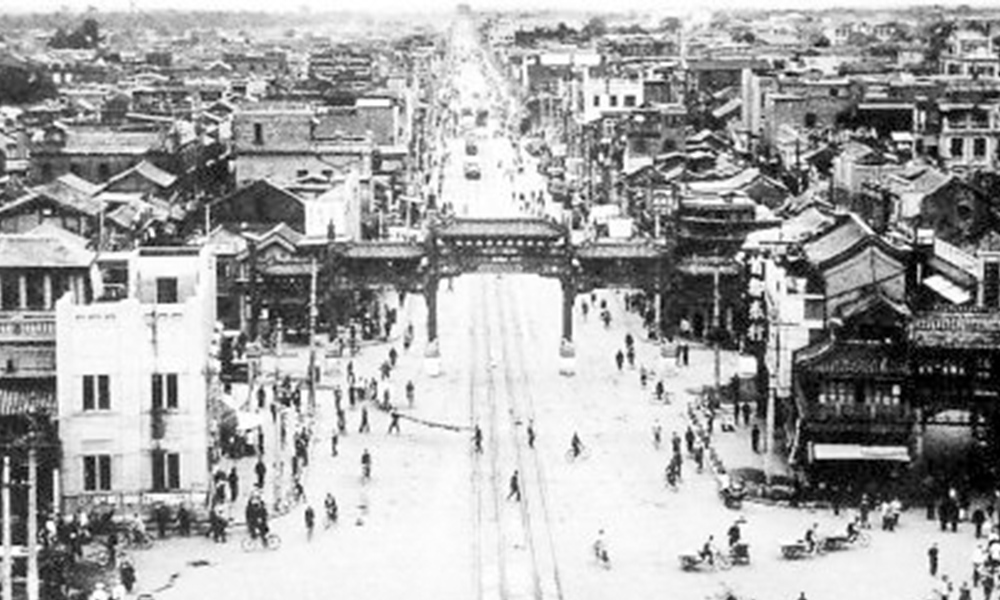

1930年代北京 前門

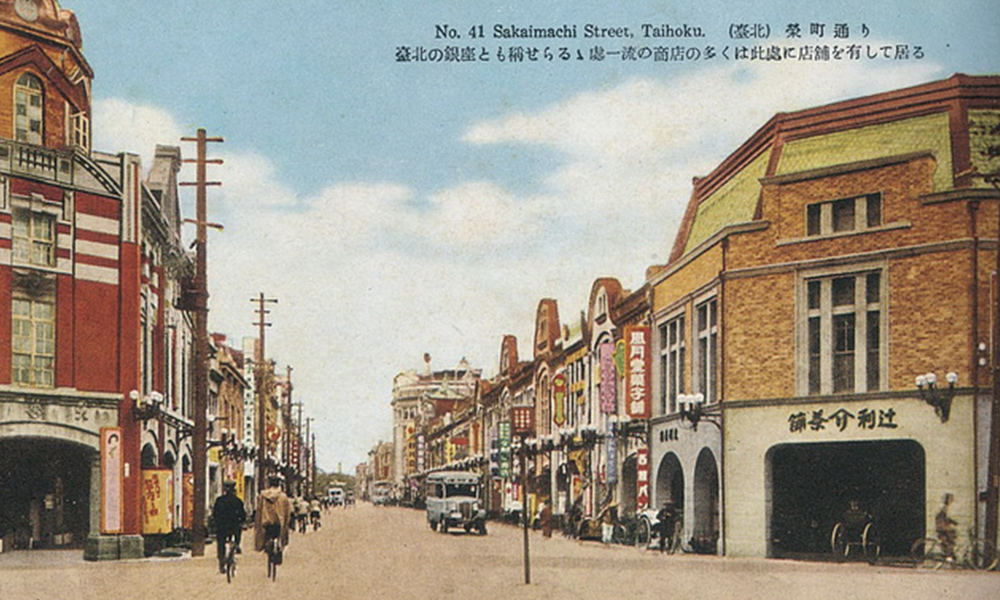

1895年台北 衡陽路

1930年代台北 衡陽路

1960年代台北 衡陽路

現在台北 衡陽路

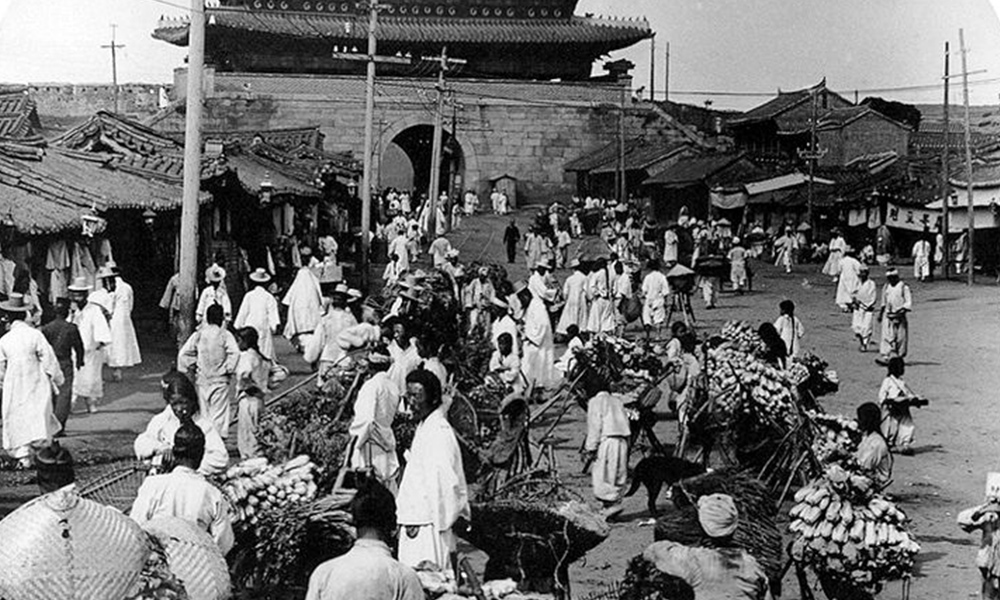

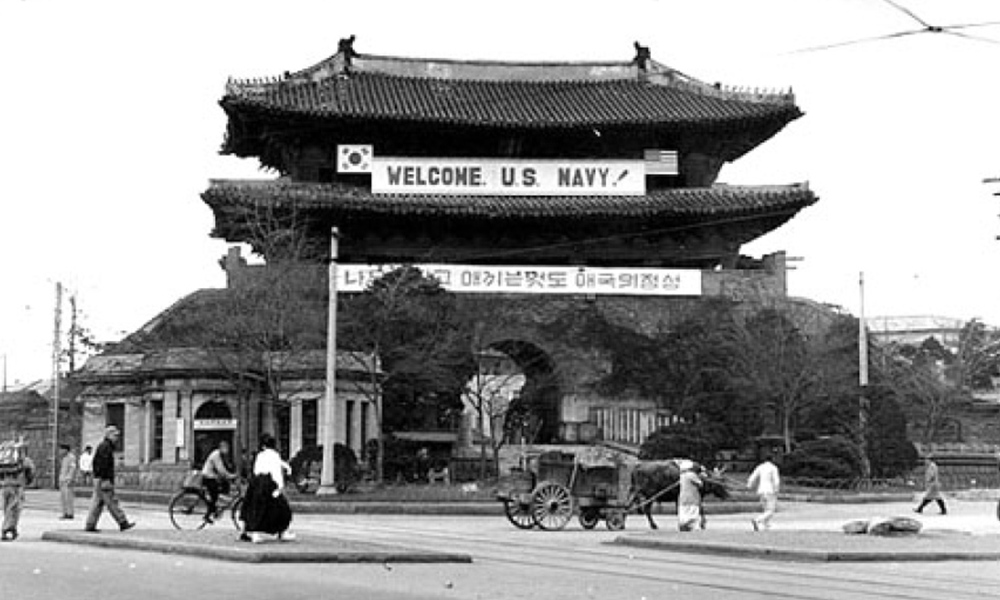

1904年ソウル 南大門

2006年ソウル 南大門

1950年ソウル 南大門

1940年代初ソウル 南大門

Ahn Sung Min, Pansori Singer

When I was thirty-two years old, I went to South Korea to study abroad. At that time, nearly ten years had passed since I started to work as a teacher for a Korean primary school after my graduation from a university. My purpose to study in South Korea was not learning Korean language but taking Pansori lessons. When I told my plan to my family, they said that I became mad as a person who gives up one of elite jobs, ‘teacher’. But at the same time, they supported my plan as saying, ‘your life is in your hands’.

I was grown up in Osaka and went to local primary, secondary and upper secondary schools. I then became a university student without deep consideration about my ethnicity as Koreans. However, at the university, I lucky meet a senior student, who was a Korean origin as me. With this coincidence, I started to grow my awareness of my root. I had a chance to re-consider something, which I left in my life. Until then, I had been thinking that I did not have any proofs of my ethnic background as Koreans, even though I was told that I was Korean. I was like an Monaka, a Japanese sweet, made of without azuki bean jam filling. I thought that I was empty, but actually I was not. I had azuki bean jam, which was the singing.

When I was a student in the second year, I began to learn Korean language under the senior student, Ms K. She offered me to have free language lessons at her home. Ms K was one of major figures for the Korean cultural movement in Osaka at that time. I began to participate in public performances with her. I played Korean folk instruments, performed theatres, and sang songs. I really enjoyed them and became involving with these activities very much. Once upon a time, when I was listing to folk music with a cassette tape, I stacked with one folk sing. It was the song called ‘My Father’s Favourite’, which my mother used to sing when she was washing my family’s clothes. I remembered that as I was a little child, I also sang the song with my mum without understanding lyrics! Yes, my ethnic sense was indeed in my mind. Songs made me to think the way, ‘wherever else I live, I would like to inherit estate of Korea as a Korean descendant…’

I didn’t have a big dream when I started practicing Pansori. I didn’t even think that I became a professional Pansori player or I would be learning to play an unusual instrument, which most people could not play. I didn’t have such ambition and determination at all. I just wanted to sing a song. I felt limit with myself, whom I could not enjoy singing fold songs, which I used to love.

I became a student of Nam He Sung (南海星) in summer in 2001. She became my master of Pansori, and was a master of ‘Sugungga’, which is fifth on the list of Important Intangible Cultural Properties of Korea. Since then, I have been participating in summer school every year. After completing my four-year studies, I came back to Osaka in 2002. However, I did not fully enjoy playing Pansori. Indeed, it is normally believed that it takes more than ten years to be a master… Therefore, I was not satisfied with my performance even though I practiced hard. In order to be a professional payer, people must start to take lessons from their childhood and has to polish their voice. On the other hand, I was already over thirty years old and I was a third-generation Japanese-Korean. It was likely that I was doing something impossible. During my lessons under the master every summer and winter holidays, I became questioning why I was taking lessons for Pansori. To be a professional? What can I do if I become a professional? Do I want to have my performance in Korea? Do I want to be listed in Important Intangible Cultural Properties as my master? No no, I don’t. Okay, then why do I keep going to take lessons… I found an answer through a performance of ‘Sugungga’ in 2006. If we perform it with a full version, the play takes around two hours and half. At that time, we aimed to shorten the programme to an hour and forty-five minutes. During our practice, my master, Nam He Sung (南海星) said to me, ‘Perform on your own, as you are Japanese-Korean.’ When I heard her words, I thought that I found something to answer.

When I went to see Pansori at the first time, I was shocked by voice of a singer. ‘How could they make such voices? If I learnt Pansori more, I attracted to its stories more and more. Pansori is not just simply a song. It has narratives. Yes, it is telling lives of ordinary people. Audiences become sympathetic with a range of characters of Pansori. They laugh, cry, and get rid of their mud in their mind. So that they can go back to their normal lives with acquiring ‘power of stay alive’. Pansori depicts people, who live together, and their lives as they are. Therefore, I believe that it has been attracting people for 250 years. ‘Pansori, which I can only perform…’ Yes, indeed, I found my identity through songs. I should sing a song and tell a story, which I can only do as Japanese-Korean. In 2002, I wrote in a broacher, ‘My dream is to sing about a story about lives of Japanese-Koreans’. My dream became true twelve years later in April 2018.

My both paternal and maternal grandparents were from Jeju Island. They moved to Osaka in the 1930s. They had never revisited the island and passed away at hospital in Osaka. I used to visit to see my grandparents’ home, when I began to learn Korean language. When my grandma peeled an apple, I said ‘komassun-mida’, thank you in Korean to my grandma. She was surprised and asked me that where I learnt the word. It was only Korean word, which I knew. Before she passed away, she had lost her Japanese completely and only could speak local dialogues of Jeju Island. She, Harumoni, also forgot about me. I regret that I did not ask her about her life – why and how she moved to Osaka. Even I did not hear about her early life in Jeju Island. In order to perform‘April Story’ this time, I did research on texts about the Jeju uprising, April 3, 1948, and explored remaining testimonies of survivors. Through this research, I even increased my regrettable feeling.

Since last summer, I have wanted to participate in a memorial service in Jeju Island to mark 70 years. I discussed with my colleague, Cho Ryoon Ja (趙倫子), a drummer, about our possibility to perform during the ceremony. After that we heard that Japanese Korean Bereaved Association of uprisings in Osaka was planning to have a memorial trip to Jeju. We told an organiser that we wanted to perform during the ceremony in Jeju. As a result, our plan was accepted in every stage of the project and finally it was decided that we were going to perform the opening at one of events of the service. The event was a meeting, Pon-pri-madan (ポンプリマダン), to share testimonies and experiences of remaining survivors. Our little hope, like if possible we would like to, became real. At the same time, we felt pressure of composing Pansori about 3 April, 1948, as if we could accomplish it or not. Amidst our mix feeling of anxiety and excitement, perhaps our fear and confidence without any reasons, we started to prepare for our performance in late autumn. First, Cho Ryoon Ja (趙倫子) wrote a script, and we together created lyrics. I also composed music with lyrics. It was our first time to do such hard work, and we hit the wall and fell down many times. We always supported each other, stood up again and again, and walked one step by step. We felt difficulty to compose Korean lyrics as a third-generation Japanese-Koreans very much. We re-realised that the greatest of melody of Pansori, which beautifully adapted for Korean language rhythm and accents. We understood how it was sophisticated and deep, which we had been singing and drumming. Moreover, we learnt the importance of having ideas, which we wanted to express, and knowing how to express them.

More than 30,000 people in the island were killed during the Jeju Uprising on the 3rd of April in 1948. How must I understand this such tragic and appalling event in the island where my grandparents were born…? ‘It was not the simple story – nothing to do with good or bad.’ When Cho Ryoon Ja was writing the script, she said to me so. The US occupied authority planned election only for south of the country, which was obvious that the plan led to divide the country into two parts. It was true that not only a number of victims, during mass insurrection by the US military government, police forces from the peninsula, and right-wing activities, including Northwest Youth League positions, were the highest, but also a large number of local people in the island were killed during the massacre of the guerrillas, which were based in Hallasan. In other words, there were many innocent people who were killed during a number of retribution attacks between the US military government forces and the guerrillas. Even there were many survivors, who suffered for mental illness brought about by trauma, and who committed suicide due to feeling guilty for surviving. There were also survivors, who feared to be seen as a Red and became silent about the tragedy. Clearly, we could not judge the event as good or bad, and could not say, ‘we will fight against the world to not have such tragedy never again’, just like a person, who stand aloof, say. Therefore, we decided to express one of our lives projects, which would memorise all victims and keep telling the story about April 3, 1948. With hope.

‘My dream is to compose Pansori about the story of Japanese-Koreans.’ Twelve years have passed since my initial plan. I finally made my first Pansori, ‘April Story’. But I believe that I needed twelve years. I would like to keep creating our stories one by one.